Manifesto 2024: Inclusive Education for All

ALLFIE’s manifesto seeks to promote the realisation of the equity, equality and the right to inclusive education for ALL Disabled people, through the necessary supports in mainstream settings. It sets out six demands of the government, to create an inclusive education system and achieve justice in action.

We urge you to Sign our Manifesto and add your comments. Our Manifesto 2024 is also available to download in various formats, including Easy Read:

- Full Manifesto (PDF)

- Full Manifesto (Text only – Word)

- Easy Read Manifesto (PDF)

- Summary Manifesto (PDF)

Our Demands

ALLFIE’s manifesto seeks to promote the realisation of the equity, equality and the right to inclusive education for ALL Disabled people, through the provision of necessary supports and adjustments in mainstream settings. This manifesto sets out six demands for creating an inclusive education system:

- Adopt an Inclusive Education legislation in the UK

- End all forms of segregated education

- Redirect government SEND funding towards supporting and improving mainstream services

- End all forms of Curriculum and Assessment systemic injustice

- Make Inclusive Education Training mandatory nationwide

- Combat Social Injustice in Education

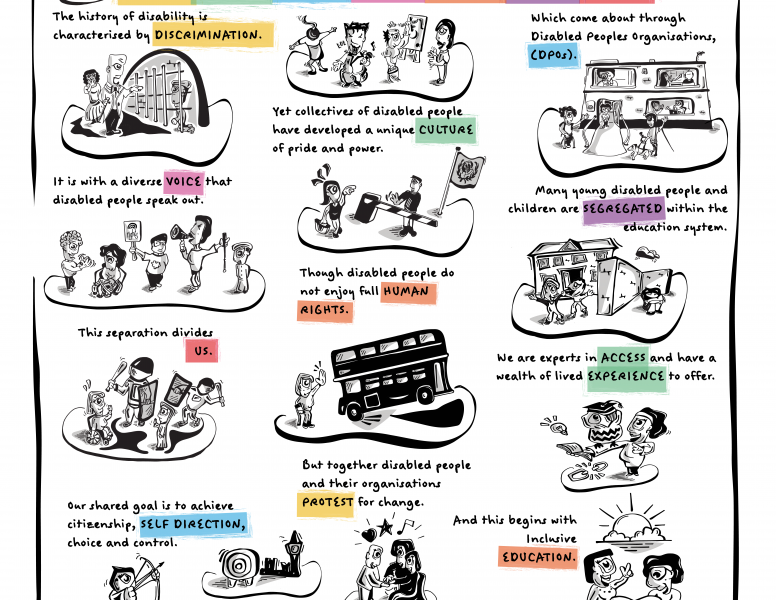

About ALLFIE

We are a Disabled People’s Organisation (DPO), led by and for Disabled people, campaigning to abolish all systemic barriers to our participation in mainstream education. For over 30 years, ALLFIE has demanded equality and equity in education for Disabled people, and their families. We know inclusion works. We believe that an inclusive education system that meets the needs of all Disabled people from childhood, and supports life-long learning, is the foundation to an inclusive society.

We campaign for the realisation of Disabled people’s right to inclusive education, in line with Article 24 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD). This Article states that Disabled people have the right to inclusive education and to participate in mainstream education with appropriate support.

Our work is underpinned by the Social Model of Disability, which states that we are “disabled” not by our impairments (such as blindness or autism) but by society’s failure to take our different needs into account. Within education, this includes systems, structures and practices that lead to our marginalisation and exclusion from mainstream educational settings and society at large. We believe that this is oppressive and a social injustice.

What we do

Our work is centred on the lived experiences of Disabled people as a process to understand and initiate ideas for our campaigns. We aim to redress power imbalances and promote Disabled people’s full and effective participation in decision-making, to bring about radical change in law and policy relating to inclusive education.

Our practice takes account of intersectionality to respond to the diverse experiences of Disabled people including other protected characteristics such as gender, race, religion, and sexual orientation as well as different socioeconomic backgrounds.

The UNCRPD and the Right to Inclusive Education

Our manifesto demands are framed within the provisions of the UNCRPD, in particular Article 24, which states:

“States Parties recognise the right of persons with disabilities to education. With a view to realising this right without discrimination and on the basis of equal opportunity, States Parties shall ensure an inclusive, education system at all levels, and life-long learning.” (UNCRPD 2006)

In 2017, its committee concluded that the UK Government is making insufficient progress in realising inclusive education, and that its present education and Special Education Needs and Disabilities (SEND) frameworks are inadequate and discriminatory. It recommended that the UK Government should:

“Develop a comprehensive and coordinated legislative and policy framework for inclusive education and a timeframe to ensure that mainstream schools foster real inclusion of children with disabilities in the school environment and that teachers and all other professionals and persons in contact with children understand the concept of inclusion and are able to enhance inclusive education.” (UNCRPD Committee 2017).

UK law and policy on inclusive education should be guided by this recommendation so that there is confidence that inclusive education settings will welcome everyone. A parent of a Disabled pupil said:

“We need to be speaking about a system that is for all, regardless of ability. In an inclusive world there wouldn’t be mainstream – there would just be education that included all.” (ALLFIE 2019)

What is inclusive education, and do you know why it is a social justice issue?

“Inclusive education isn’t just about dreaming about the future. We don’t just want you to plan for the next generation. We want justice and liberation for those currently in segregated education” (ALLFIE’s Our Voice Young Disabled people, 2024)

Inclusive educational settings are those where non-disabled and Disabled people (including pupils/students labelled with “special educational needs”) learn together in mainstream nurseries, schools, colleges, universities and adult learning in the same classrooms, attending the same classes, lectures and seminars. This means the education system must adapt to include Disabled people and should not require Disabled people to adapt to the education system. Thus, inclusive education involves the removal of the structural and systemic barriers Disabled people encounter in mainstream education settings. It also involves addressing the systemic oppression of Disabled people in mainstream education settings. As articulated by the UNCRPD Committee:

“Inclusion involves a process of systemic reform embodying changes and modifications in content, teaching methods, approaches, structures and strategies in education to overcome barriers with a vision serving to provide all students of the relevant age range with an equitable and participatory learning experience and environment that best corresponds to their requirements and preferences.” (UNCRPD General Comment no. 4 on Article 24).

Inclusive education is a social justice issue because it is about confronting the underlying systemic barriers that perpetuate the marginalisation and discrimination of Disabled people within the education system and wider society. This includes tackling issues such as inadequate funding for inclusive education (especially in under-resourced neighbourhoods), discriminatory policies and practices, disproportionate disciplinary actions, and barriers to higher education for Disabled people. It also includes tackling the barriers that hinder Disabled children and Young people labelled with “complex needs” from accessing mainstream schooling, both in the classroom and in extracurricular activities. In the words of Gray Group International (2024):

“Social justice aims to counter these challenges by ensuring equitable resource distribution, dismantling systemic obstacles, and fostering environments where all individuals can thrive.”

We recognise that it will take time to move from the current education system to one that is inclusive, and it will require radical changes in thinking, policy and practice. As part of a transition process, separate special education settings can be repurposed and used as community resource centres that offer outreach services to support Disabled people in inclusive mainstream education settings and provide community access to resources and equipment.

How Disabled people are being failed by the current education system

Throughout history successive Governments have carried out various reforms to the education of Disabled people and its provisions. Current provisions are based on the Children and Families Act 2014, which sets out a presumption that children should be in mainstream education. Despite this, Disabled Children and Young people, especially those of us who are labelled with “complex needs”, encounter barriers to accessing mainstream education. Barriers are experienced both in the classroom and in extracurricular activities.

In March 2023, the Government launched the Special Education Needs and Disabilities (SEND) and Alternative Provision (AP) Improvement Plan: Right Support, Right Place, Right Time. This plan reiterates the Government’s commitment to invest £2.6 billion for local authorities to open 133 new free special schools between 2022 and 2025. This goes against the intention of Children and Families Act (2014) ‘presumption of mainstream education’ and of achieving inclusive education for ALL Disabled people in mainstream settings.

Meanwhile, schools and local authorities are not adequately resourced to support, or make adjustments, for Disabled children and young people in mainstream settings. Some local authorities are failing to give pupils the support that is recommended in their EHC plans. This is driving Disabled children and young people into special schools or substandard alternative provisions such as PRU (pupil referral unit) and EOTAS (education otherwise than at school) and is denying them the opportunity to access and experience mainstream schooling.

Most local authorities have financial deficits in their overall education budgets – known as Dedicated Schools Grant (DSG) – because the budget for SEND provisions has not increased since 2015 when the government extended the age range of young people who qualify for SEND Support. The Department for Education (DfE) has provided additional funding and support for local authorities with the largest DSG deficits through the Safety Valve and the Delivering Better Value (DBV) programmes.

However, parents have expressed concerns that children and young people are at risk of being denied the SEND Support that they are entitled to by local authorities on the Safety Valve programme since they make a commitment to contain spending on SEND provisions in exchange for this financial assistance. There have also been press reports suggesting that local authorities participating in the DBV programme may face targets to reduce the number of EHC plans. The Government’s response to the latter concerns has not reassured the disability community, parents and other stakeholders that this will not be the case.

The Government plans to replace A levels and T levels with a Baccalaureate-style qualification called the Advanced British Standard in England in the next 10 years. This qualification will combine A levels and T levels into a single qualification, including compulsory study of English and Maths to age 18. Students will also be required to study five subjects instead of the usual three and have more teaching hours in the classroom.

High absenteeism in schools has been a major challenge during the post-pandemic period, with Disabled pupils registering higher absenteeism rates compared to non-disabled pupils. The Government response is to introduce a plan for new ‘attendance hubs’ run by schools with low absenteeism records. The Government also plans to introduce legislation that requires schools to share their daily school registers. We fear that these measures will make schools less welcoming to Disabled children. Current schools that welcome Disabled children, will become more reluctant to continue doing so, as it will be another factor that will impact their school ratings.

Disabled people are overrepresented among those who are in segregated education, not in employment or not in training. Too many Young Disabled people are labelled as NEET. Young Disabled people are also disadvantaged in transition from school to employment workplace training opportunities, with the Supported Internship being exploitative. This is a cause and consequence of marginalisation.

Our Demands – Justice In Action

The following is a list of ALLFIE’s demands in relation to what needs to be done to achieve the vision of an inclusive education system.

1. Adopt an Inclusive Education Legislation in the UK

We demand the recognition of inclusive education as an inherent right for ALL people, and for the voices of Disabled people to be heard and respected on matters of inclusive education.

To achieve this, the Government should:

- Adopt legislation that domesticates the UNCRPD and recognises inclusive education in mainstream settings as a right for ALL Disabled people in line with Article 24 of the UNCRPD. This legislation should:

- Secure Disabled people’s right to equal access to education and learning in mainstream settings at all levels of education and promote life-long education for Disabled people.

- Prohibit all forms of discrimination and systemic injustices against Disabled people in education provision.

- Have measures to address the systemic exclusionary barriers that result in Disabled people being denied equal access to education and learning in mainstream settings.

- Aim to end all forms of segregated education and dual registered provisions in recognition that inclusive education is the foundation to an inclusive society.

- Withdraw all reservations to Article 24 of the UNCRPD and follow the EHRC position with the recognition of a just and equitable inclusive education system for everyone.

- Engage Disabled people and Disabled People’s Organisations (DPOs) as equal partners from the formulation through to the implementation and evaluation of all legislation on inclusive education. This should be done in line with the principles of co-production and collective work, embedding the slogan of the Disabled People’s Movement: Nothing about us without us.

2. End all forms of Segregated Education

We demand clear goals to systematically phase out special nurseries/schools/ colleges/units and other segregated educational settings, prioritising inclusive learning environments for everyone.

To achieve this, the Government should:

- Learn from the good practice and success of other countries (such as Australia) in systematically phasing out segregated schools/colleges/ units, as tools to move forward on making inclusive education a human rights matter for everyone.

- Stop all initiatives to build new special schools and redirect resources towards achieving inclusive education for all Disabled people in mainstream settings.

- End all segregated post-16 programmes such as Supported Internships because these are exploitative.

- Develop a plan to systematically phase out special nurseries/schools/ colleges/units and other segregated educational settings while at the same time ensuring that all Disabled people achieve their right to inclusive education in mainstream settings with appropriate support and resourcing. This will be a move towards the progressive realisation and implementation of the right to inclusive education, in line with the UNCRPD.

- Provide sufficient resources to ensure the accessibility and provision of adjustments for Disabled people at all mainstream educational settings. Ensure that all mainstream educational settings are equipped and resourced to address the support needs of all Disabled people.

- Adopt a unified and better coordinated approach to addressing Disabled people’s educational, health and care needs.

- Support Disabled people in building relationships with peers in mainstream settings. At the same time, ensure that Disabled people are protected from all forms of violence, abuse, torture, bullying, humiliation, and degrading treatment in education settings.

Inclusive education should be achieved within and across the entire education system. All segregated educational institutions, classrooms and programmes should be systematically phased out including at institutions of higher education. Disabled people should be given meaningful and equitable opportunities to participate in apprenticeships, internships and other work-based learning programmes. This should be realised by providing the support that Disabled people require to do so.

3. Redirect government SEND funding towards supporting and improving mainstream services

We demand that inequalities in SEN provisions and disability services are immediately addressed, aiming to dismantle barriers to mainstream education for ALL Disabled people and ensuring provision of consistent and accessible services.

To achieve this, the Government should:

- Establish robust and efficient systems and procedures for delivery of SEN support and disability services that enable Disabled people to enrol and remain in mainstream settings, with the aim of phasing out all segregated schools and units.

- Establish and implement policies and guidelines that are guided by inclusive education principles to ensure consistency and equality within and across the education system.

- Appropriately fund and resource educational settings to ensure Disabled people are not denied admission, excluded or placed at a disadvantage compared to other students.

- Remove all targets that would place Disabled people at a disadvantage within the education system such as Safety Valve and the Delivering Better Value programmes.

- Develop and implement accountability systems for assessing and determining good practices of inclusive education within mainstream settings.

4. End all forms of Curriculum and Assessment systematic injustice

We demand action to address systematic injustice by changing both the curriculum design and the administration of assessment systems, ensuring just and equitable outcomes for all students.

To achieve this, the Government should:

- Develop more dynamic curriculum and assessment systems that do not disadvantage Disabled people on account of their impairments and the lack of appropriate support.

- Re-evaluate the objectives of education and learning to ensure that they are not discriminatory to Disabled people.

- Adopt inclusive teaching practices and stop teaching practices that are discriminatory to Disabled people.

- Address intersectional biases within the curriculum design and teaching practices.

- Adopt flexible assessment and examination practices that do not disadvantage Disabled people.

- Provide adequate resources and support for Disabled people in examinations and assessments.

- End parallel programmes and curriculums designed for Disabled people only.

- Engage Disabled people with the relevant skills and experience on how to make the curriculum and assessment system inclusive.

- Ensure that the introduction of the British Advanced Standard does not disadvantage Disabled people, reducing their chances of progressing to further-, higher-education and employment.

5. Make Inclusive Education Training mandatory nationwide

We demand comprehensive inclusive education training for all teachers and administrators.

To achieve this, the Government should:

- Make training and professional development on inclusive education compulsory in teacher training and have systems for measuring performance.

- Develop and implement in-service training, professional development and capacity building programmes for teachers and administrators to ensure that they are aware of Disabled people’s right to inclusive education and address attitudinal barriers (including stereotypes and misconceptions).

- Ensure shared accountability of addressing and supporting the delivery of SEND provisions and disability services within and across educational settings.

- Provide the required resources and support to effectively teach and support Disabled people in achieving inclusive education.

6. Combat Social Injustice in Education

We demand action to address all forms of social injustice in education, including intersecting disadvantages.

To achieve this, the Government should:

- Adopt educational policies and practices that address all forms of social injustice in education, recognising the diversity of Disabled people’s lived experience and the intersectional disadvantages that some Disabled people experience due to their gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and socio-economic background. For example, a Black Disabled girl might face discrimination due to a combination of the two or more of her separate protected characteristics (race, disability and gender) as well as other intersecting experiences.

- Give due recognition to the intersection of segregated education provisions, poverty, poor housing, and social capital and put in place appropriate policies and measures to achieve more equitable outcomes in the education system.

- Ensure that the education system responds to the needs of Disabled people from different cultural backgrounds and fosters respect for this diversity.

- Increase representation of Disabled people from different backgrounds in teaching staff and administration.

Glossary

Accessible – a product, service or building that is designed, or has been modified, in a way that allows Disabled people to use it or access it without encountering accessibility barriers. Accessibility is about ensuring that everyone can access information, products, services, and environments in a way that is inclusive and equal.

Advanced British Standard – a new educational framework that will combine A-levels and T-levels into a single qualification for 16- to 19-year-olds in England. Under this qualification students will be able to take a mix of technical and academic subjects.

A-Levels – subject-based qualifications that can lead to university, further study, training, or work. You normally study three or more A levels over two years.

Alternative Provision (AP) – education outside of mainstream settings, arranged by local authorities or schools.

Attendance hubs – government initiative aimed at reducing school absences. These will not address the wider issues of school non-attendance.

Dedicated School Grant – a ring-fenced specific grant that supports local authorities’ Schools budgets.

Delivering Better Value (DBV) programme – a Department for Education (DfE) initiative focused on local authorities reducing spend on EHC plans.

Disabled People’s Organisation (DPO) – an organisation run and controlled by Disabled people.

Education other than at school (EOTAS) – the education or special educational provision of children or young people outside of a formal educational setting.

Education, Health and Care plan (EHC plan) – a legal document describing the special educational needs of a child or young person’s aged up to 25 as well as the support they need, and the outcomes they would like to achieve.

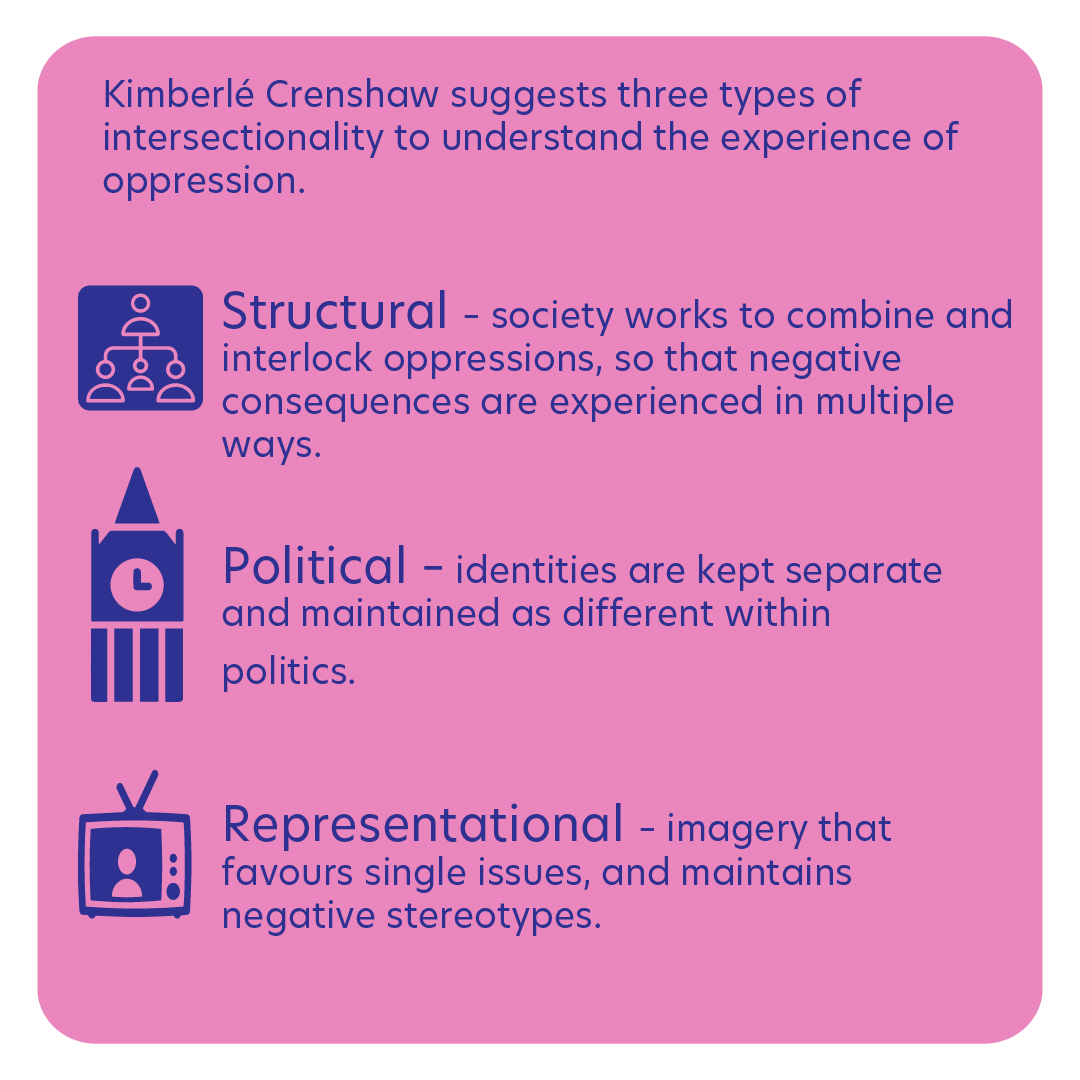

Intersectionality – people’s different experiences based on protected characteristics such as age, gender, race, religion or sexual orientation and socioeconomic background.

Marginalisation – Marginalisation means to treat a person or social group as though they are of less value than others. This can happen when individuals are treated differently from the majority and experience exclusion and segregation.

NEET – Young people (aged 16 to 24 years) not in education, employment or training (NEET).

Oppression – being treated cruelly or prevented from having the same opportunities, freedom, and benefits as others.

Safety Valve programme – a Department for Education (DfE) initiative focused on local authorities reducing spend on SEND provisions.

Segregation – Disabled people are placed away from ordinary experiences with others. For example, Disabled children placed in special schools are given an inferior education to non-disabled people, such as EOTAS.

SEND – Special Educational Needs and Disabilities.

Social Model – The social model of disability is a way of viewing the world that was developed by Disabled people. The model says that people are Disabled by barriers in society, not by their impairment or difference.

Socioeconomic background – A person’s socioeconomic background is measured through specific factors such as income, education, class and occupation. It refers to the background you are from, including the class and education status of your parents.

Systemic barriers – established policies, procedures or practices that discriminate against people and prevent them from participating fully in education, employment and other areas of life.

Teacher – anyone who performs a teaching role in a nursery, school, college, university or adult learning setting.

T-Levels – a two-year qualification for 16 to 19-year-olds designed in collaboration with employers. Each T Level is equivalent to 3 A Levels, with the aim to support the young person to develop their skills, knowledge and to thrive in the workplace.

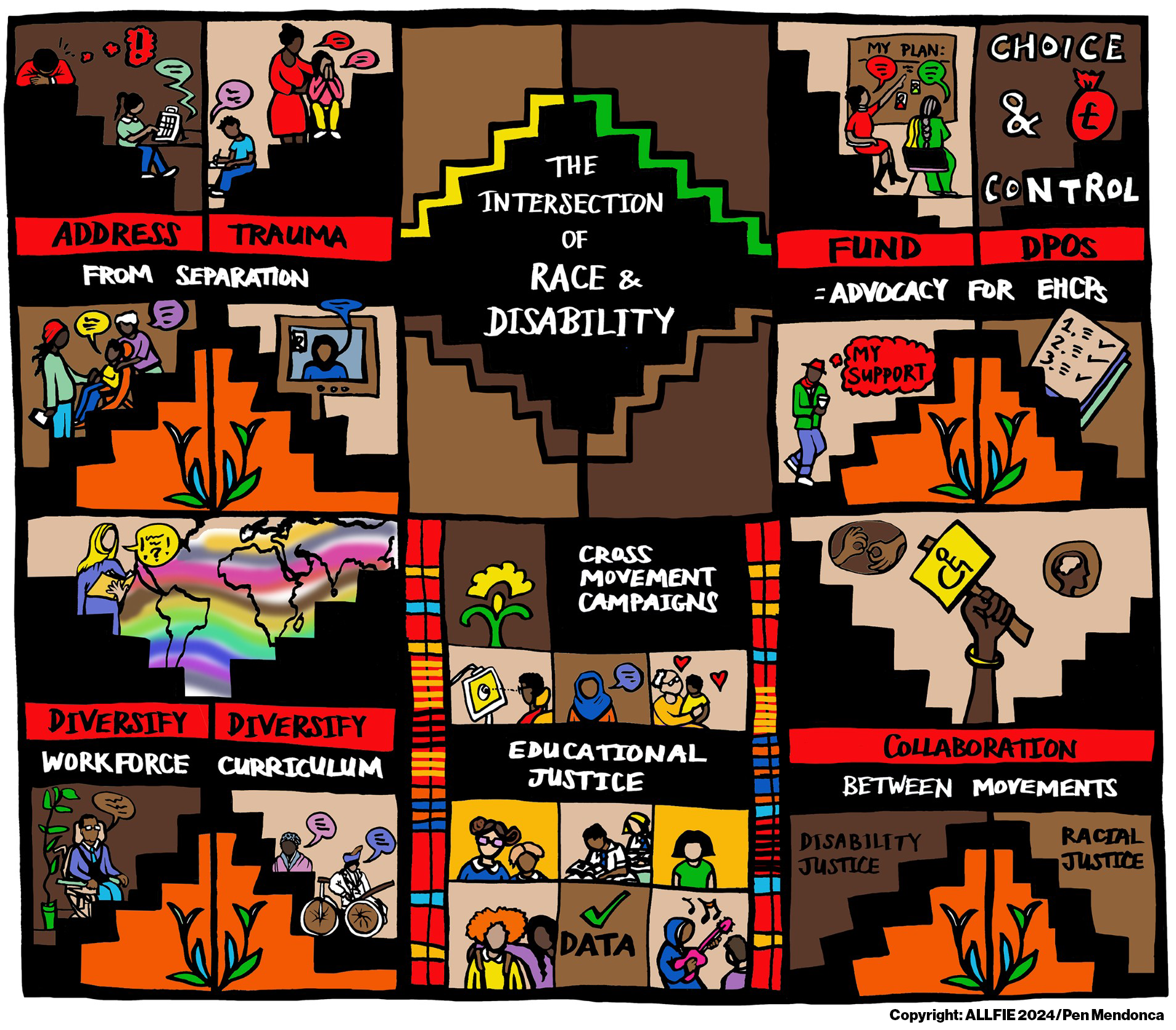

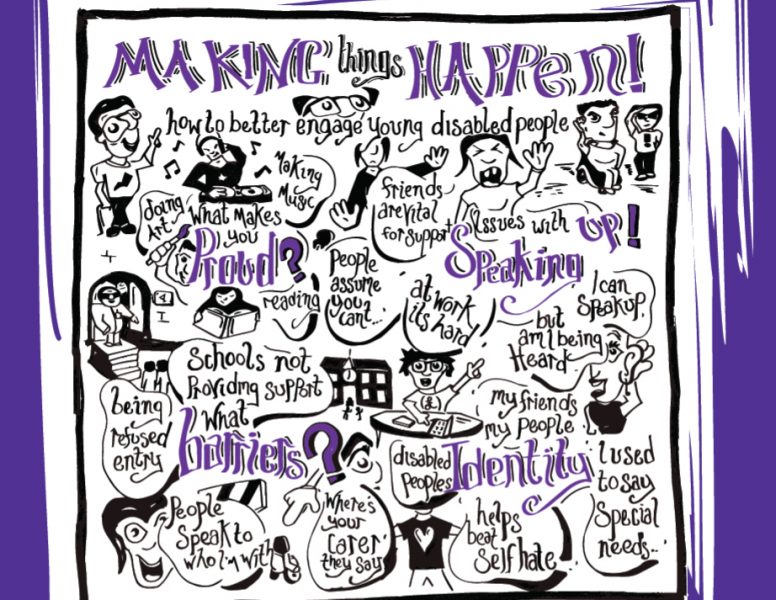

Lived Experience of Black/Global Majority Disabled Pupils and their Families in Mainstream Education

ALLFIE’s research project about the lived experiences of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils and their parents about schooling. It explores experiences of mainstream school placement, participation, support and attitudes of school staff, and makes important recommendations to address issues.

- Download full report (pdf): Lived Experiences of BGM Disabled Pupils in Mainstream Education

- Easy-read pdf: EASY-READ Lived Experience of BGM Disabled Pupils in Mainstream Education

- Summary pdf: SUMMARY Lived Experience of BGM Disabled Pupils in Mainstream Education

Summary

This research is about the lived experiences of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils, aged 11-16 and their parents about schooling. It explores experiences of mainstream school placement, participation, support and attitudes of school staff.

The research found that there is inadequate support for Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils and their families in terms of advocacy, peer support to share information and provide clarity on entitlement, help to empower them and protect children’s right to mainstream education.

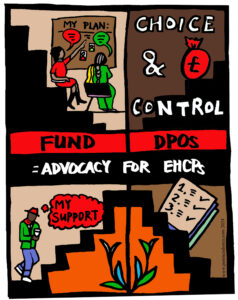

Children and young people told us that they would like;

- To have better choice and control over their support, so as to be better able to join in and participate in the range of school activities and opportunities.

- An end to the separation of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils and recognition of their proud intersectional experiences, not ones based on deficit.

- To have a say in writing school rules and policy, to coproduce practice and build a sense of belonging.

Parents highlighted their concerns to us in terms of;

- That they feel they have little support and limited or no choice about where and how their children are educated.

- An excessive use of disciplinary procedures and practices of surveillance towards Disabled pupils and Black children that result in negative consequences or exclusion.

- Difficulties navigating an education system that is complex and often overlooks intersectional experiences of disability and race.

The current lack of support makes it hard to address any tensions around the intersections between disability and race when navigating the education system. To address these issues, we make the following six recommendations.

Recommendations

- Improve understanding and recognition of intersectional experiences.

Increase the representation of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils within the education setting and social justice work. - Tackle the trauma experienced through grouping and separation.

Encourage work in schools to address the effects and trauma caused by segregation on all pupils. - Promote independence, choice and control in EHCPs.

Develop advocacy support to ensure EHCPs achieve independent living and human rights of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils. - Challenge negative attitudes and promote positive representation.

Diversify the teaching workforce, profile more diverse experiences in school and promote learning about intersections of disability and racial justice. - Expose harmful disciplinary procedures and surveillance.

Build a campaign between disability and racial justice organisations to highlight and end disciplinary procedures that lead to exclusion and discrimination of young people. - Challenge segregation, promote participation.

Highlight school intake discriminatory practices affecting Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils, showcase practical and applied solutions that demonstrate how inclusive education can and does work elsewhere.

Acknowledgements

The Alliance for Inclusive Education (ALLFIE) Research Steering Group would like to thank the Runnymede Trust for commissioning a research study which explored the educational experiences of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils (aged 11-16) and their parents. Your support has been instrumental in driving this project forward, and your commitment to advancing research in this area is appreciated.

We also thank Disabled Black Lives Matter (DBLM)[1] for offering their expertise, support, time and commitment to engage in conversations about this research. They have provided direction and offered a critical voice and meaningful debate about research questions and emerging issues. We wish to extend our gratitude to note-takers and Karima Ali (a former project researcher).

We want to express our sincere gratitude to all stakeholders and research participants (Disabled pupils and their parents) within the London region. This research would not have been possible without their support, and we hope that the issues raised in this report show that their lives matter. We are sincerely grateful for their participation.

Finally, we acknowledge the context in which the issues raised in this report reflect the broader struggles for disability justice by Disabled Activists, campaigners and scholars and the continuing battle for inclusive education.

ALLFIE Research Steering Group

- Dr. Navin Kikabhai, Chairperson of ALLFIE, (University of Bristol)

- Dr. Themesa Y Neckles, DBLM member, (University of Sheffield)

- Tasnim Hassan, Trustee of ALLFIE and PhD Student/Researcher (Durham University)

- Michelle Daley, Director of ALLFIE

- Saâdia Neilson, Disability Justice Consultant and DBLM member

- Iyiola Olafimihan, Disability Justice Consultant and DBLM member

- Okha Walcott-Johnson, Disabled Children and Parent Advocate and DBLM member

[1] Disabled Black Lives Matter is a group of people that campaign to address racial and intersectional inequality of Black Disabled people. DBLM, who situated themselves alongside Black Lives Matter, aim to encourage other Disabled People’s Organisations (DPOs)/movements to aim for racial and intersectional equality.

List of Abbreviations

ALLFIE: Alliance for Inclusive Education

AP: Alternative Provision

DBLM: Disabled Black Lives Matter

DPO: Disabled People’s Organisation

EHCP: Education, Health and Care Plan

ESN: Educationally Subnormal

ITE: Initial Teacher Education

PRU: Pupil Referral Unit

SEN: Special Educational Needs

SENDCo: Special Educational Needs Disability Coordinator

SEND: Special Education Needs Disability

TA: Teaching Assistant

UNCRPD: United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

Glossary of Terms

Ableism is based on a hierarchy of ability through notions of able-bodiedness (and able-mindedness); favouring, valuing and normalising the standards of non-disabled people.

Black/Global Majority Rosemary Campbell-Stephens coined the term to promote a sense of collective belonging while addressing the inappropriateness of terms like BAME/BME. Black/Global Majority serves as a unifying term to change understanding and language regarding individuals from Black, Asian, Brown, dual-heritage, indigenous to the global south, and those racialised as ‘ethnic minorities’ (source: https://www.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/-/media/files/schools/school-of-education/final-leeds-beckett-1102-global-majority.pdf).

Disability is often understood as a problem, a tragedy, and often about something that is ‘wrong’ with a Disabled individual. It is a consequence of society’s failure to accommodate the entitlements and rights of Disabled people. The social model of disability interprets disability as discrimination, exclusion and social restriction. Disability as discrimination involves identifying barriers and oppression and recognising power relations.

Disabled people/persons/pupils is an identifying and collective term for a group of people with impairments who identify as Disabled people.

Disabled People Organisation (DPO) is an organisation which is run and controlled by and for Disabled people, and centres lived experiences, uses the social model of disability to address disablism and ableism and applies the UNCRPD.

Disablism is a consequence of disability discrimination—oppressive or abusive behaviour based on the belief that Disabled people are inferior to non-Disabled people (source: https://demos.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/files/disablism.pdf, p.9).

Education Health and Care Plan (EHCP) covers individuals from birth to age 25. This legal document outlines the educational needs and arrangements necessary for a child to enable children/young people to access education and achieve their goals.

Inclusive Education, also called ‘inclusion’, embraces the idea of education that includes everyone, promoting a learning environment where non-disabled and Disabled individuals, including those labelled with ‘Special Educational Needs,’ learn together in mainstream schools, colleges, and universities (source: https://www.allfie.org.uk/definitions/what-is-inclusive-education/).

Independent Living Disabled people are in control and can choose how they care for themselves.

Intersectionality is the idea that different social categories, such as race, class, gender, and disability, interact to produce various experiences.

Learning Support Assistants are individuals allocated to support the learning that takes place in classrooms. This support can be provided in one-to-one situations or small groups. Their role may also involve assistance with tasks such as reading, feeding at lunchtime, or attending to medical needs. These tasks vary and depend on the individual pupil’s needs.

The Medical Model of Disability typically views Disabled people as a problem and tends to label individuals by using medical and pseudo-scientific terms. Disabled people are viewed as disabled by their impairments (e.g., blindness, deafness, wheelchair-user or autism). An objective of the medical model of disability is to cure a person’s impairment, often through medical interventions. When using the medical model of disability, the question of how a Disabled person fits into society would disappear. This approach suggests that society does not need to change to accommodate Disabled people, reinforcing discriminatory attitudes and behaviours. https://www.allfie.org.uk/definitions/models-of-disability/medical-model-disability/

A Personal Assistant (PA) is a person employed by a Disabled individual to assist with tasks, including getting dressed, socialising with friends; enabling the person to achieve independent living and live in their community.

Pupil Referral Units (PRU) / Units / Alternative provisions are segregated provisions designed outside the mainstream schooling system and intended to not place pupils in mainstream schools.

Racism happens when others treat people negatively because of their skin colour, ethnicity or nationality. There are different types of racism, such as institutional, direct and indirect racism. For example, direct racism could be calling someone horrible and hurtful names based on the colour of their skin. Institutional racism creates systemic barriers that disadvantage others because of the colour of their skin, ethnicity or nationality. Indirect racism (discrimination) can occur, for example, when there are policies that apply to everyone but disadvantage a group of individuals because of their skin colour, ethnicity or nationality.

Social justice concerns systemic and structural societal inequalities, addressing equity, equality, inclusion, access, quality, rules, and values and promoting difference and well-being for all people.

Social Model of Disability, a term coined by Mike Oliver in the 1980s, provided the understanding that Disabled people are seen as disabled not by their impairments (such as blindness or autism) but by society’s failure to take their needs into account. (source https://www.allfie.org.uk/definitions/models-of-disability/social-model-disability/).

Special Educational Needs and Disability, ALLFIE defines Special Educational Needs as relating to Disabled individuals regarding the requirements and arrangements for additional educational support.

Special Educational Needs and Disability, in legislative terms, is defined as that which calls for ‘special educational provision’ and a young person is said to have ‘learning difficulties’ if they have a ‘greater difficulties than the majority of children of the same age’ or ‘has a disability which either prevents of hinders the child from making use of educational facilities of a kind provided for children of the same age’. Disability is defined as ‘physical or mental impairment which has a substantial and long-term adverse effect on a person’s ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities. For Disabled people, these definitions are inconsistent and problematic and typically place the ‘problem’ of disability within the individual. (refer to Disability above)

A Teaching Assistant (TA), sometimes referred to as a Learning Support Assistant, is a person who usually assists with all elements within the class and works more closely with the classroom teacher. Their role may also involve reading, assisting with feeding at lunchtime or attending to medical needs. These tasks vary and depend on the individual pupil’s needs.

Territorialised boundaries are associated with the theorisation of space and can be of multiple forms (for example, cultural, of the body, identities). Territorialised boundaries and spaces, related to geopolitics and globalisation, often involve disputes (sometimes violent) and arguments which reflect power struggles. It can affect the role of states and sovereign power. Segregated educational spaces are routinely territorialised, involving vested interests and issues of subordination and power.

Velcro support is a term which describes the possible adverse effect of the role of a TA or LSA who has been assigned to an individual. In this situation, an adult TA or LSA often becomes a barrier, preventing the young person from making friendships with their peers or engaging in everyday interactions by being ‘stuck together’ and not giving space. Velcro support often prohibits more natural peer–support relationships occurring in and outside of schools amongst their peers.

Introduction

This small-scale qualitative research aimed to critically examine the lived experiences of Black/ Global Majority Disabled pupils in the mainstream education system. ALLFIE, a DPO, conducted this research, and its members formed a research steering group of Black/Global Majority Disabled people with lived experience. We intended to understand the disproportionate impact of a failing education system on the often-ignored lives of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils through their intersectional experiences. Our positionality centred on ALLFIE’s social justice approaches to the social model of disability, disability, lived experience, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disability (UNCRPD) (on Inclusive Education, Article 24) and intersectionality.

The report encompassed focus group interviews with parents and Black/Global Majority Disabled school-aged children. Through participants’ lived experiences of attending a mainstream school setting, this report acknowledges how their lives are directly affected by systems of disablism and racism. It adds to the current inclusive education debates, challenges existing inequalities within the education system and seeks to improve outcomes for Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils.

Given the issues raised in this report, it is essential to acknowledge how disability is framed. For example, in the field of inclusive education, there is an overarching focus on how the ‘requirements’ and ‘needs’ of Disabled pupils are met to enable them to achieve their potential. According to Runswick-Cole (2008) and Beckett (2009), these discussions are framed within an ongoing discourse between a medical model (which focuses on the individual’s impairment and is deficit-driven) and a social model (which prioritises the removal of barriers). This report adopts the position that ‘disability’ is ideologically constructed (Kikabhai, 2022) and that it is the organisation of society that disables people. As Oliver (2009) articulated, over two decades ago:

… the barriers disabled people encounter include inaccessible education systems, working environments, inadequate disability benefits, discriminatory health and social support services, inaccessible transport, houses and public buildings and amenities and the devaluation of disabled people through negative images in the media – films, television and newspapers (Oliver, 2009, p.47).

This report recognises that currently, how various stakeholders seek to improve school life, educational environments and the way multi-agencies work together (e.g., parents, local authorities, health and social care services, Integrated Care Boards [ICBs]) to accommodate various ‘differences’ (Naraian and Schlessinger, 2017) is contested. Indeed, as the literature review highlights, there is increasing segregation under the guise of so-called ‘Alternative’ provision (HMSO, 2023).

Alongside critically examining the lived experiences of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils’ schooling, the research investigates the intersection of disability and race within this context. This report aims to understand how Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils and relevant stakeholders navigate their educational experiences by identifying connections and themes to enhance the inclusive education movement.

The remaining section of this report focuses on a review of related literature; the methodological approach adopted, key findings and a discussion of the data and recommendations.

Literature Review

This literature review explores the importance of school placement, Education, Health and Care plans and raises critical questions about the continued and persistent inequalities in the education system. In this sense, the Special Educational Needs Disabilities (SEND) system has become even more adversarial and bureaucratic. The review also explores the issue of teachers’ attitudes towards racial equality and draws attention to the problem of representation, or lack thereof, within the teaching profession. The review explores disciplinary procedures and surveillance of behavioural policies and their connection to Disabled people’s experiences of restraints. Finally, this literature review refers to social participation and its relationship to how Disabled people are perceived.

School Placement and Intake

Since the start of modern mass state schooling, school placement for Disabled People and those currently described as having Special Educational Needs has a long history of segregation (Humphries and Gordon, 1992), often in the guise of treatment (Kikabhai, 2014), which later shifted to a discourse of needs (Borsay, 2005; Haines and Ruebain, 2011). Research related to school placement tends to focus on parental choice (parental preference in legal terms) between special educational provision and mainstream settings (Satherley and Norwich, 2021; Bagley et al., 2001; Bajwa-Patel and Devecchi. 2012). There are several vital factors framing this dualistic debate. These include a school’s willingness to accommodate a child’s educational needs, the availability of resources, the special educational teaching (pedagogy), class size, quality of parents-school communication, parents’ and teachers’ attitudes, the proximity of the school to home, and the well-being of the child (Rix and Sheehy, 2014; Mawene and Bal, 2018).

Being a signatory (and ratifier) to the UNCRPD (United Nations, 2006), the United Kingdom has placed a Reservation on Article 24, which primarily means that ‘special’ education is part of its offer. Of course, this contradicts the United Nations’ requirement for Member States to demonstrate the progressive realisation of inclusive education. The UNCRPD (United Nations, 2006) states that Disabled students participate in mainstream settings and have equal access to private and public educational institutions.

Nevertheless, persistent educational barriers exist, including unfair assessments of children’s abilities, exclusion, and inadequate resource allocation, impeding children’s access to mainstream education (Runswick-Cole, 2008; Soorenian, 2019). Moreover, as stressed by Kikabhai (2022), a recent United Nations observation drew concerns about the continued dual education system that segregates Disabled pupils based on parental choice. Compounding the issue of resource allocation, funding for mainstream schools has also been heavily influenced by performance-based criteria and meritocracy.

Research by Leckie and Goldstein (2018, p.22) highlighted that ‘the higher the proportion of disadvantaged pupils in a school, the more [the school] will effectively be punished for the national underperformance of pupil groups.’

Alongside the concern about the UK’s Reservation on Article 24, the number of Disabled pupils in so-called ‘special’, ‘alternative’ and ‘free’ schools has increased as thousands of new special school places were confirmed (Dept for Education and Coutinho, 2023). For example, the UK Government’s (UK GOV, 2023) latest figures for 2022/23 indicate that in England there has been an increase of 87,000 pupils said to have SEN, the percentage of pupils with an EHC plan increased to 4.3% from 4.0%, the percentage of pupils with SEN but no EHC plan has increased to 13% from 2.6%.

Arguably, the increasing number of segregated provisions deprives Disabled pupils of their right to a fully resourced inclusive education system. There is a disproportionate number of Disabled and Black pupils enrolled in segregated school environments. The early work of Coard (1971) identified this trend, using the notion of ‘educationally subnormality’ and how Black Caribbean children were disproportionately placed in ESN settings during the 1960s-70s.

This trend continues in a modified form known as SEND (Skiba et al., 2008; Wallace and Joseph-Salisbury, 2022). In addition, the recent SEND and Alternative Provision Improvement Plan (HMSO, 2023, p.9) introduces National Standards as an approach to delivering funding bands and tariffs.

These standards suggest that Disabled pupils labelled with complex needs are more likely to be placed in a segregated ‘special’ school as a result of these new funding bands and tariffs. A pressing concern arises around how this approach to schooling inadvertently perpetuates racism and ableism. This is because the evaluation of children for admission to special schools is linked to schools’ subjective assessment of pupil’s behaviour, emotions, and communication levels.

Experiences of Education, Health, and Care (EHC) Plan

An Education, Health, and Care (EHC) Plan is “a legal document which describes a child or young person aged up to 25 special educational needs, the support they need, and the outcomes they would like to achieve” (Council for Disabled Children, 2023, p.1). Cochrane and Soni (2020) examine the experiences of implementing and using the Education, Health, and Care (EHC) Plan, emphasising the growth of multi-agency working, which remains complicated and disjointed. This captures many positive experiences and challenges, including parental involvement. Whether the processes genuinely centre children and young people, evaluate the role and knowledge of school staff, and recognise disparities in experiences based on age and different educational stages is still debatable.

Despite aspirations to adopt a holistic approach with the EHC plan, it has been criticised for its reductionist and deficit-oriented characteristics, with a notable omission of the environmental aspect (Hunter et al., 2019). The implementation of the EHC plan faces challenges. For example, families’ access to a Personal Budget from Local Authorities to meet their child’s needs lacks transparency, and schools are expected to grapple with this process unsupported (Adams et al., 2017; Blatchford and Webster, 2018; Cochrane and Soni, 2020).

Given the significance of the Government’s SEND and Alternative Provisions Improvement plan, it is disappointing that the report failed to take an intersectional approach. However, it is noted that the report did ‘highlight some disparities concerning certain characteristics such as place, gender and race’ (HMSO, 2023, p.43). The report notes their absence in these areas. It fails to point out the consequences of homogenising Disabled people and their families to a singular characteristic and social background, as well as the way this report is implemented.

The report has committed to using the Regional Expert Partnerships to engage ‘… the voices of all children and young people with SEND or in alternative provision and their families are effectively heard, and no group is disadvantaged …’ (HMSO, 2003, p.43). This is particularly disconcerting, especially given that as of June 2023, ‘Travellers of Irish heritage’ and ‘Black Caribbean’ students had the highest prevalence of individuals with EHCPs.

There has also been a constant increase in appeals challenging EHCP-related decisions. A consistent trend emerges when examining the outcomes of SEN/D tribunal appeals, as 96% of the outcomes in the 2021/22 period were in favour of the appellant (same as the previous year). Notably, this does not make any reference to race or ethnicity.

Teachers’ attitudes, competence, and workforce

Research indicates that teachers in mainstream educational settings generally have a positive, inclusive attitude. However, its implementation needs to be revised. For instance, Center and Ward (2006) highlight that there is a lack of confidence in being able to provide support, and Avramidis and Norwich (2002, p.129) emphasise that there is ‘no evidence of acceptance of a total inclusion or ‘zero reject’ approach’, finding that this is selective. About diversifying the curriculum and supporting diverse needs, there has been a notable surge in the desire to promote racial equality (Klein, 1993; Hall, 2021; Batty et al., 2021). However, despite this increased interest, it has become increasingly evident that educators lack the confidence and training to implement more diverse content effectively (Petitions Committee, 2021; Joseph-Salisbury, 2020). Perhaps even more ignored, references to disability remain relatively minor and not given appropriate consideration, as pointed out by Beckett (2009).

Further, Kikabhai (2022) suggests that within diversity work, not only is disability intentionally ignored, but it is also silenced and erased. It has been felt that staff have had limited training to support inclusion – particularly in universal learning design (Dolmage, 2017). This highlights teachers’ considerable challenges, including time and training limitations and insufficient guidance in addressing ‘challenging’ or ‘sensitive’ subjects. In light of this, the University of Manchester and Runneymede Trust’s Making History Teachers briefing (Lidher et al., 2023) highlights the urgent requirement for the Department of Education to establish structures enabling extensive professional development for all educators.

Enhancing teacher training is crucial to prepare and support teachers adequately. For example, Lidher et al. (2023) underscore the necessity to update both the Teachers’ Standards and Initial Teaching Education (ITE) with a more substantial commitment to addressing anti-racism, inclusion, and diversity issues. It is known that there are significant tensions with ITE when it comes to Disabled people and so-called ‘Fitness to Teach’ standards that often act as a barrier rather than an enabler to the teaching profession, particularly for individuals who identify as having mental health difficulties (differences), experience distress, identify as neurodivergent individuals, and/or are survivors/users of mental health/psychiatric services (Pattinson and Kikabhai, forthcoming).

There exists poor representation within the teaching workforce, which is linked to lowered expectations for Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils. For example, there is a ratio of one white teacher for every 13 white pupils. In contrast, a stark imbalance exists of one Black teacher to every 42 Black students, exacerbated in other domains and senior roles (Hillman, 2021; Wallace and Joseph-Salisbury, 2022). It is necessary to question that both of these datasets lack intersectional overlap and knowledge regarding whether teachers are Black/Global Majority Disabled people. There is also an omission of disability data obtained for teachers (Office for Statistics Regulation, 2023). Hence, it can be strongly inferred that there is a significant lack of educators with diverse and intersecting experience.

Disciplinary procedures and surveillance

There are other inequalities in behavioural policy. There are three specific groups of children and young people who are disproportionately affected by behavioural policies in schools, namely, those identified as having SEND, individuals from racially diverse communities (including Black students and those from Gypsy, Roma, and Traveller backgrounds) and students from under-resourced backgrounds (Gillborn et al., 2013). Between 2018 and 2022, in England and Wales, data from the Children’s Commissioner revealed at least 2,847 documented strip-searches of children conducted in schools and outside schools before arrest under stop and search powers, with the report highlighting a significant six-fold over-representation as 38% of the strip-searched children were Black, a group constituting 5.9% of the population (Dodd, 2023). This is compounded by the Child Q scandal and the perpetuation of negative stereotypes through Prevent Duty (Home Office, 2023; Runnymede, 2023; Zempi and Tripli, 2022). Additionally, law enforcement has been assigned to areas ‘with higher numbers of pupils eligible for free school meals, which correlates with higher numbers of Black and ethnic minority students’ (Runnymede, 2023, p.2).

Disabled students have a higher probability of being subjected to restraint or seclusion in school, as indicated by recent reports indicating that 88% of reported incidents involved children or young people, including students identified as having SEN/D (The Challenging Behaviour Foundation, 2019; Hodgkiss and Harding, 2023). Regarding monitoring the use of restraints in schools, the Equality and Human Rights Commission inquiry (Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2021) highlighted confusion and inconsistency in school restraint policies; schools varied in how they record restraint incidents, especially in distinguishing between types.

Many are uncertain about specific forms of restraint, and some do not promote categorising incidents by protected characteristics. Additionally, as Worth (2013) highlighted, Disabled students can be heavily monitored by supporting [sic] staff in controlled environments. Interestingly, Ktenidis (2023, p.1) contends that some problems associated with TA support relate to structural inequalities that recreate exclusion. Further still, Ktenidis (2023), drawing upon the experiences of Disabled students in secondary school, makes the point that TAs carry out their duties ‘under the guise of support’ and often aim for normalisation. It has been known that there are disadvantages to using TA support. For example, Gerschel (2005, p.71) referred to the ‘velcro’ model in terms of recognising the possibility of students becoming emotionally dependent on the TA.

Social Participation

A crucial aspect of school life involves social inclusion, as frequently depicted in literature through attitudes, approval, a sense of belonging, and the formation of friendships (Carter and Hughes, 2005; Petry, 2018). Attitudes towards disability significantly shape whether Disabled students receive more positive or negative experiences (Freer, 2023). Research tends to be more skewed in highlighting persistent barriers, irrespective of the type of education setting, such as challenges developing meaningful friendships, experiencing bullying and exclusion due to being perceived as different, non-disabled peers reluctant to befriend Disabled people and those labelled as having SEN, feelings of isolation, and a lack of opportunity (Shah, 2007; Edwards et al., 2019; Woodgate et al., 2020; Helman, 2009; Batorowicz et al., 2014).

Despite this dominant narrative, researchers such as Avrandis (2012) and Shah (2007) evidence some positive experiences. A recurring message emphasises the significant role that inclusivity-focused environmental elements, such as school staff and resources, can play in mitigating marginalisation (Baker and Donnelly, 2010; Anaby et al., 2012; Avranidis, 2012).

In summary, while it is evident that additional efforts are needed to address the educational barriers experienced by Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils, young people and their parents, this review aimed to highlight emerging issues that could provide insights into their experiences.

Multiple layers contribute to shaping the experiences and narratives relevant to this group. Institutionally, neoliberal, pursuing profits, and systemic deficit-driven inclinations affect the availability of support and the procedures for obtaining it and, consequently, shape student placements and intake and entitlements under the EHC plan.

This influence extends to the teaching workforce and various agencies, characterised by punitive and controlling practices aimed at achieving ‘normalcy,’ a lack of confidence, and enforceable legislation in supporting diverse student requirements and limited literacy regarding issues of race and disability. These factors collectively contribute to a societal narrative that detrimentally affects Disabled students’ overall sense of belonging within mainstream educational settings.

Methodology

This section explains the methodological approach that was adopted during the research. It presents its conceptual frame, which primarily describes how knowledge is gained. It also discusses online focus group interviews, the analytical approach, and research ethics issues. We were interested in critically examining the lived experiences of schooling for a small group of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils in the mainstream education system.

Conceptual Framework

The research adopted an interpretivist perspective within a philosophical and conceptual framework of social constructionism (Burr, 1995), using focus group interviews as the sole method of data collection. We were particularly interested in gathering qualitative data to understand the lived experiences of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils and their parents about mainstream schooling.

We were interested in challenging taken-for-granted ideas about schooling, seeking to understand the daily interactions of pupils and parents with schooling staff, recognising that these are socially, culturally, and historically situated. In Berger and Luckaman’s (1991) terms, we are interested in the social construction of everyday life, and in this context, with an analysis of schooling, particularly about how the lives of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils and their parents are constructed.

Focus Group Interviews

Fitting within adopting social constructionism, focus group interviews allow participants to ‘… articulate those normally unarticulated normative assumptions’ (Bloor et al., 2001, p.5). As such, we were keen to understand the barriers, challenges, strategies and participation experiences of the individual participants and their collective experience.

The two online focus group interviews were arranged with four (4) Black Disabled young people/children aged 11-16 years of age and three (3) parents of Black Disabled pupils/young people. Initially, potential participants were recruited through social media and parent networks. Greenbaum (1998) said these focus group interviews would be more accurately termed mini groups. Uniquely, each of the online focus group interviews, mini groups, were facilitated by four members of the research team; this included an interviewer (moderator), a safeguarding lead who was available if any of the participants felt they wanted time-out and somebody to talk to, a timekeeper, a coordinator who provided technical support and a notetaker.

All participants were sent a focus group interview schedule (Appendix D). Both online focus group interviews lasted approximately 60 minutes and were digitally recorded and transcribed. The digital recordings were sent to a professional transcription service for verbatim transcripts. All focus group participant names were anonymised, we recognised the cultural sensitivity around using appropriate pseudonyms rather than engaging in acts of cultural and identity (agency) erasure.

Analysis

Once verbatim transcripts were available, key themes were identified across and within each of the transcripts. The research adopted critical discourse analysis to focus the group on topics, ‘… tapping into group life …’ (Bloor et al., 2001, p.50), searching for similarities, noting differences, and particularly interested in analysing social and political inequalities.

Ethical Considerations

Participants were provided with an Information Sheet (Appendix B) which described the purpose of the research, what the participation would mean, how participant data would be protected and stored, reassurance about the confidentiality and anonymity of the data, and participants’ right to withdraw without having to provide a reason.

All focus group participants were sent a consent form (Appendix C) before participating in the research. Online focus group interviews were recorded via Zoom and stored in password-protected folders on ALLFIE’s server. Issues of confidentiality were particularly stressed during online focus group interviews.

During focus group introductions, the interviewer stressed this particular point; the specific focus Group interview extract is:

Extract: FG160623

11 … In terms of confidentiality, I’m sure you

12 would appreciate that, given that we’re going to be talking as a group,

13 we may not know each other. And so, therefore, after the focus group,

14 we would ask you to refrain from talking about the contents of this

15 particular interviews with other people. And I’m sure you’ll be close to

16 other people and it’ll probably be very tempting to talk to somebody

17 and if you needed to talk to somebody, please reach out to us again

18 if you just needed to debrief or anything like that. …

Another ethical consideration was the late arrival of one of the pupils and their parents, who had connected via their mobile phone network during their focus group interview.

This caused some intermittent network failure and delays in re-connectivity. Fortunately, technical support was available to assist and facilitate reconnection.

Findings, Analysis and Discussion

The main priority of the findings, analysis, and discussion is to develop knowledge about the experiences of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils and their parents in mainstream education to inform campaigns and advocacy that take a social justice approach. This section focuses on five issues drawn from the findings and offers a discussion and analysis in conjunction with the previous literature. The five issues relate to school placement, experiences of EHCP, teacher attitudes, disciplinary procedures and surveillance, and social participation.

School placement and setting

Pupils provided insightful reflections on what it is like to study alongside non-disabled peers within a mainstream setting. Noeline made a notable observation that highlighted the importance of how she conveyed her findings about the separation of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils and their exclusion from the larger school community.

To illustrate this point, Noeline raised the following:

… there’s a person in year seven uses a wheelchair, but I don’t see them around that much.

(Noeline, Focus Group Interview, 2023)

Noeline continued to elaborate on the extent of separation between the pupils, with some of the Disabled pupils being placed in different parts of the school building, with required authorisation, explaining that:

[There’s] a place where wheelchair and Disabled pupils go there, and nobody’s allowed there, it’s locked… Like only there’s, there’s not a buzzer. The teacher has to get the card.

(Noeline, Focus Group interview, 2023)

This is worrying, as Kikabhai (2023) noted. These territorialised boundaries, part of the landscape of social power, maintain social order and control. It seems that the effect of this practice creates internalised oppression that reinforces the marginalisation of racialised and non-racialised Disabled people.

Our discussions with parents largely revolved around the parents’ decision-making process and their experiences throughout the school journey. Parents’ experiences primarily presented the main barrier to admission to mainstream school was compounded with them having to position a more impairment-specific priority, disregarding the intersections of disability, race, gender and other experiences of their Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils.

This is highlighted in parents’ decisions in determining an appropriate school for their children based on the school’s SEND services and support (Rix and Sheehy, 2014; Mawene and Bal, 2018).

This point was notably clear from Omnira’s experience:

I went through a process of choosing the school, so I contacted the schools I thought would be good for them, and what I looked for was their SEND and Provision Department. So, what does their special needs department look like? What do they do? How educated are they in terms of SEND? So, I contacted the schools on my list, and I did like a process of elimination. I chose what I feel is the best of the worst. I don’t feel any school really encompasses what it is to be a disabled child because I don’t think that it’s personalised and it’s just based on their systems. (Omnira, Focus Group interview, 2023)

It is also noted that parents’ attempt was not to negate considerations pertaining to their child’s race, gender and social class background in their search for a school. Omnira explained it this way:

… I didn’t look at their experience in terms of ‘race’. I looked at it in terms of practice in the school practice because I couldn’t look at it as ‘race’ because there’s no commonality between us, there’s no education between us, so I couldn’t, and I didn’t know any other disabled children that were Black that was in that school. (Omnira, Focus Group interview, 2023)

This indicates that these parents’ experience navigating the SEND system defaulted to suit White Disabled pupils.

This was also compounded by a lack of peer support for Black parents of Disabled pupils, as highlighted by Njoki:

I think at the time, what I didn’t have was a good network in terms of other parents who had additional needs, and for me, I think that was probably the biggest thing because, actually, that is a really good indicator when you talk to people about the actual experiences.

(Njoki, Focus Group interview, 2023)

Zina’s strategy involved searching online and tapping into social networks, and what is particularly significant is hearing from shared experiences of the support received that ultimately helped inform their decision:

Once I’d had my eyes set on that started looking at their SEND programme and what their SEND legislations they had at that school. I also have a friend who’s a Social Worker, and she recommended the same school to me. She said, ‘ One thing I can say about that school is their SEND team is amazing’. And then, when I went and spoke to them as well, I experienced the same. I felt like, based on what they were telling me, based on what they said, that they had and what they could offer, it was a great school, and this was all before my son even had his diagnosis, but I was like pretty sure he was [going to] get it. (Zina, Focus Group interview, 2023)

It was also important for some parents that their children enrolled in a school that was also attended by other family members, which plays a vital part in reinforcing a social sense of belonging and relationships, as mentioned by Zina:

I saw one of my cousin’s sons … he had just started Year 7 when my son was in Year 6, and he was going to a school that he really, really liked and he and my son are quite similar, even though he’s not autistic, they have similar interests and quirks, so to speak.

(Zina, Focus Group interview, 2023)

None of the parents in the focus group had considered the idea of placing their children in special schools: their first choice gravitated towards choosing mainstream education, as demonstrated by multiple parents:

I’ve never considered anything outside of a mainstream school. (Zina, Focus Group interview, 2023)

… my son’s never been to anything other than a mainstream school. (Njoki, Focus Group interview, 2023)

I wanted them [twins] to be in mainstream school because I didn’t believe that being in a special school was going to be adequate for them based on how their needs were present. (Omnira, Focus Group interview, 2023)

In conclusion, the findings reveal distinct perspectives on the issue at hand. From the pupils’ point of view, a noticeable sense of separation and differential treatment emerged as significant themes. When considering the parents’ experiences, it became evident that their primary criterion for choosing a school for their Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils was the school’s SEND services, often overlooking the complex intersections of disability, race, gender, and other experiences.

It was also noteworthy that the experiences of Black/Global Majority parents of Disabled pupils were faced with limited choices available to parents, whether this was from lack of information or peer support networks. From this, the evidence demonstrates that schools often dictate the selection of the child, rather than parents having a say in choosing the school, a point articulated almost two decades ago (Tomlinson, 2004).

Experiences of EHCP and receiving support

Out of the four pupils, it was noted that 3 of them had EHCPs with access to a Teaching Assistant (TA) and other support services. Notably, all three pupils raised concerns about the implementation of their EHCPs. One of the concerns echoed the principles of the Independent Living Movement, which emphasises the ability to choose and control your support. It also became evident through the focus group interview with pupils that their support staff needed to share their experiences, particularly regarding shared backgrounds and interests. For example, Iskander spoke about the issues that led to the breakdown in the relationship between them and their TA. For Iskander, it appeared that the breakdown of the TA support extended to supporting a different football team; he said:

Basically, I would just like [choose Teaching Assistant]. I would. … like him to be that I would like him to support Liverpool. (Iskander, Focus Group Interview, 2023)

There were also concerns that the TA did not fully understand the support needs of pupils. For Iskander, it was particularly annoying when they did not get their entitlement to the support they needed; he specifically said:

Yeah, [I was] really annoyed … he would help me with my work. Like what I found with recent TAs is that they don’t like every time I want, like, every time I ask them for a walk, they always… And I and I don’t really like that. That’s one of the main reasons why I didn’t get along, obviously.

(Iskander, Focus Group Interview, 2023)

Iskander’s experiences with his TA aligns with the point raised by Whitburn (cited by Ktendis, 2023, p.4) that TAs ‘perpetuate the special education traditions in inclusive education’, highlighting limited agency and lack of centring the student’s voices in their support.

Interestingly, Whitburn (2013, p.158), from an Australian context, found that one of the significant shortfalls of TA support (paraprofessionals) is that school cultures tend to adopt discourses of deficit and that ‘educators’ tend to rely on TAs because their own ‘shortcomings in non-inclusive pedagogical practices’.

Additional concerns were the frustration of getting a teaching assistant and sharing this provision with other pupils, which impacted their support.

Iskander articulates the issues this way:

So basically, yeah, they [the TA] wouldn’t give you space. They would always like. They would always be on to you, and they would never like… if you ask for help, they’ll cut you off. And then and then they’ll go. And then they’ll go to another student. (Iskander, Focus Group Interview 2023)

Eta, who did not have an EHCP, shared her experiences of the barriers and challenges that they were experiencing at school. When asked about the ideal person to support them in school, Eta said that they would like:

Someone who listens and understands what you say and tries to explain things in different ways is kind and funny and doesn’t keep us behind [during the] break [period]. (Eta, Focus Group Interview, 2023)

Regarding parents’ involvement and experience with the EHCP planning, experiences were varied. For example, not all of the parents’ children had an EHCP; some were currently going through the process, and another parent was assessing the situation to help decide the appropriate action to take. Zina shared that:

… We’ve recently had a… handover meeting with the person that assessed my son and his school SEND team and his Head of Year. And we had a meeting about what he needs and what I’m asking for, etcetera, and they were very helpful. They seem very open, and they already suggested things there, and then they’ve really put certain things in place. He doesn’t have a plan. I do think we will go for that eventually, but he’s doing okay. He’s doing okay. (Zina, Focus Group Interview, 2023)

Njoki, another parent, recounted their journey of implementing their child’s EHCP and conveyed, “My son has an EHCP, and that has been helpful, and it was perfect for him.”.

Njoki elaborated on their experiences, highlighting the complexities involved in this process. She particularly emphasised the challenges encountered during the transition from primary to secondary school, which introduced distinct structures, mechanisms, and considerations related to the EHCP implementation.

Njoki disclosed that:

So, because he was at [primary] school, that was already well built and suited to his needs, if that makes sense. So yeah, they had a really good, you know, ethos across the school, in terms of, you know, supporting children of additional needs. … It’s a very nurturing environment. His teacher is, I think she’s trained as a SENCO … So, for example … [it] wasn’t articulated in the EHCP that he needed one-to-one … I realised when he transitioned…he needed one-to-one … but then when we moved to school, certain issues would start to arise. Even though we’d had a transition meeting with this one, had articulated that these are the provisions that were in place, then the school actually hearing that and doing that because of course, we know that, you know, so the section I say we not everyone does. But what I’ve learned is that section F is really crucial to pinning down some of those things that, you know, your child may need, and I think in terms of that transition process when you’re moving to a school, that. The reality is you don’t know how your child is going to respond… You can do as much research as you can on all of those things, but actually, when they move into that setting, you know they’re then faced with changing lessons every 50 minutes. You know, and all of these different factors. It’s a completely different setting, and so, therefore, what you’ve got in the EHCP is really important… And anyway, that was my experience. (Njoki, Focus Group Interview, 2023)

In summary, the preceding sections have delved into the experiences of both pupils and parents as they navigate the educational system, particularly concerning the practical aspects of EHCPs. In the context of pupils’ experiences, the significance of having a choice and control over their support staff has been highlighted. However, it is noteworthy that the actual implementation of TAs tends to be more aligned with special educational practices.

Turning to the parents’ perspective in this section, many nuances have been observed in their decision-making processes, particularly during the transitions from primary to secondary school. It also highlighted instances of intersectional erasure, such as race, disability and other background characteristics within the education system. This showed up in the way parents considered the type of support they anticipated that their child would be receiving while at school. This differentiation manifests in numerous ways; it would require consideration of factors such as class sizes, subject-specific variations, alterations in the learning environment, adjustments to timetables, and more – all of which collectively influence a student’s daily schooling experience.

Teachers’ attitudes, competence, and workforce

Pupils extensively discussed their perceptions of teachers’ attitudes and the curriculum and consistently believed their voices went unheard. When asked about what kind of teacher would be preferred, Nyima expressed that:

And maybe a teacher that would actually listen to students and, erm, give in to students’ needs. Someone that listens and actually cares about their work and my education. (Nyima: Focus Group Interview, 2023)