Inclusive Education in Malta

In the late 90s Malta began to move towards a more inclusive, community-based education system. On a recent visit Richard Reiser met Education Officers and representatives of the Malta Federation of Organisations of Persons with Disabilities (MFOPD), to visit and research education facilities including University of Malta and Dingli Sccondary School – here’s what he discovered.

Malta is a small country of three islands in the Mediterranean, 80 miles south of Sicily. It was a British Colony for 250 years and retains some cultural similarities but also differences: being Maltese speaking and more religious, with a strong national pride and focus on family and conservatism. Malta has a traditional single gender education system based on streaming and selection, with a school population of 55,000 (493,500 total population).

Education in Malta is well resourced with 5.1% of GDP spent on education and an average secondary class size of 20. Education is largely delivered through the compulsory system comprising: 150 state schools; 34 church schools; 18 independent schools.

Three resource centres act as special schools for full or part-time students. These looked likely to die out at one point but, more recently, student numbers have greatly increased. While some children attend these resource centres full-time due to parental choice, others have no choice. Unfortunately, centres have retained the role of special schools and investment “geared to their new and expanded role of providing professional support to regular schools in meeting special educational needs” (Salamanca Statement 1994), has not taken place.

Since 2010 state schools have been organised geographically, through pyramidal colleges comprising: one secondary school; one or two middle schools; six to ten primary schools.

In church schools the state pays for teachers’ salaries and support services, with parents asked for a voluntary contribution. In recent years state schools have become co-ed. The independent schools are fee paying.

In 2014, a ten-year ‘Framework for Education Strategy for Malta’ was launched to increase participation, community involvement and inclusion, and support educational achievement and retention. A system of “banding” was reintroduced at the end of year 4 (age nine), with benchmark exams in English, Maths and Maltese replacing the equivalent of the 11+ exam and students being ‘set’ according to marks obtained in these exams.

Recent figures from the European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education Report show over 96% of students statemented in Malta attend mainstream inclusive classes – the equivalent for England is 47.8%. The level of Statements is around 5.5% in Malta, compared to 3.5% in England – this figure is rather high.

Nearly all of the school population attend their local school and age appropriate classes, with only 160 attending special school. There are, however, also resource bases developed around nurture group principles in primary schools and learning support zones in secondary, with specially trained teachers for social and emotional issues – currently one for primary and four for secondary schools (including Dingli Secondary school, featured below). In addition, 32 children with significant autism attend a specially commissioned foundation two days a week with Learning Support Educators (LSEs) to undergo a group TTEACH type programme. The effect of this provision is very low exclusions.

Rather than implementing inclusive pedagogies in class teachers tend to expect help from outside class usually in the figure of an LSE. The provision of LSEs is provided by a Statementing Board that schools and parents apply to for either full-time, shared, or shared in the same class support.

The Board is appointed by the Minister of Education and made up of SEND professionals, mostly those working within the education directorate. The LSEs are encouraged to attend University of Malta’s Department for Inclusion and Access to Learning for training to gain a diploma, recently upgraded to a degree. Other institutions also offer training courses. One particular course is of dubious quality. Many of the older teachers have not undertaken effective training in inclusion. In recent years there has been a big increase in LSEs to 2800 for 3800 children, using the bulk of increased the SEN budgets, despite rolls falling. The LSEs protest there is not always the necessary teamwork between them and teachers to facilitate the inclusion of all students. A student with a statement of needs is considered to be the responsibility of the LSE.

One issue with this system is that school students ‘become dependent’ on their LSE but are only allowed one year with each, rather than transferring through phases with the same one. Additionally, informal communication and planning between teachers and LSEs causes a disconnect which undermines whole school’s collaborative approach. There seemed a willingness from teachers to learn what was necessary, not with a coherent pedagogy of inclusion but piecemeal around particular students needs. There is an Inclusion Manager from the Directorate of School Support who coordinates LSEs in several schools and is part of leadership in schools, monitored practice, and ensures Individual Education Plans are constructed, monitored and annually reviewed.

The IEPs are, in practice, designed by LSEs using a software package, and according to diagnosis, based on the medical, deficit model of disability.

Case study

Dingli Secondary School in northern Malta has 486 students, of which 30 recieve LSE support. This includes 13 students receiving 1:1 support.

Dingli Secondary School in northern Malta has 486 students, of which 30 recieve LSE support. This includes 13 students receiving 1:1 support.

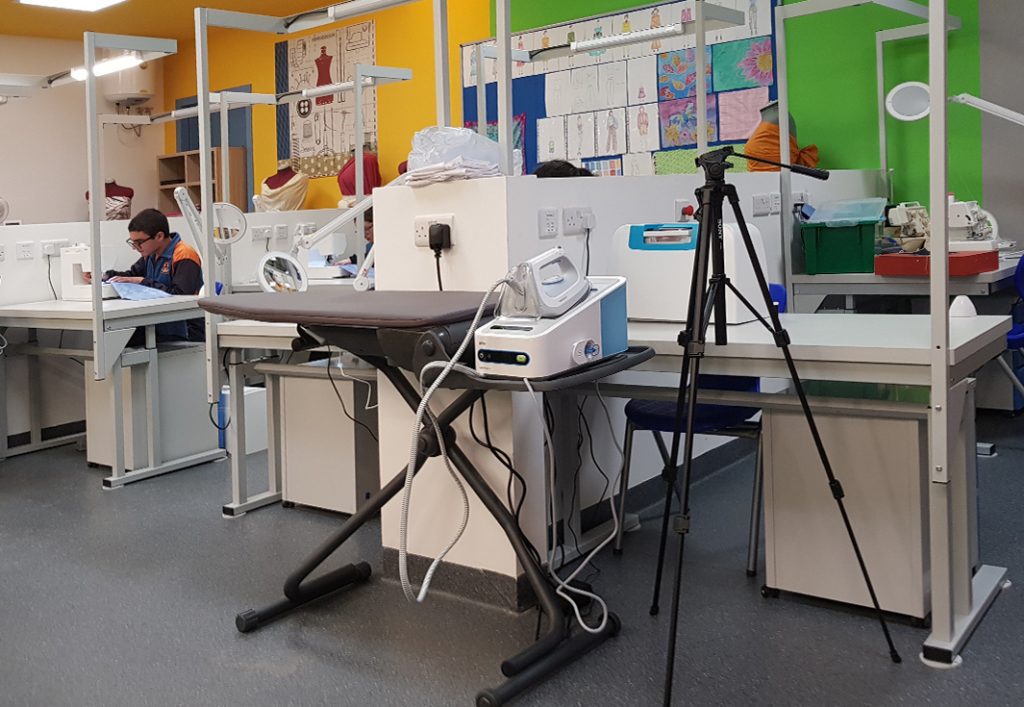

It is a spacious new build campus with lifts and wide corridors. The Principle explained that in the last two years they have introduced (as all secondaries), a vocational/practical based curriculum for those more suited to it, alongside the academic. Training takes place alongside a meeting with middle school teachers to sort out a lap top and raised diagrams, with class teachers giving notes on a pen drive.We met Sheranice, a girl who uses a rollator and the lifts to get about. She liked the school, had two best friends and seemed to have an ambivalent attitude to her LSE as she wanted to be more independent.

We saw very well resourced specialist areas, including a hospitality suite comprising restaurant, kitchen and accommodation, a food lab, and areas for video/photography and communication, textiles, craft, electronics and engineering. Other than streamed Literacy, Maths and Science, all other subjects in Year 9-11 are mixed ability, though we think banding still applied. Different weight is given to assessment through course work, projects and exams varying from 60% /40% to 40% /60%.

In the Learning Support Zone (LSZ) children attend ongoing 2×2 hour sessions per week, with progress measured via Boxall profile. Focussed groups are run on appropriate behaviour, friendship and anti-bullying, with strong evidence of improved behaviour dealing with social and emotional issues. A favourite was a ‘punch bag’ that was well used for getting rid of aggression.

In the Learning Support Zone (LSZ) children attend ongoing 2×2 hour sessions per week, with progress measured via Boxall profile. Focussed groups are run on appropriate behaviour, friendship and anti-bullying, with strong evidence of improved behaviour dealing with social and emotional issues. A favourite was a ‘punch bag’ that was well used for getting rid of aggression.

My conclusion coincides with the 2014 European Agency Audit, the issues of which largely remain, despite subsequent initiatives to improve inclusive approach:

- The UN CRPD Article 24 has not been incorporated into Maltese Law

- The resourcing approach is largely deficit/medical model and not a human right approach, particularly the resourcing model of individual Statementing needs replacing

- A narrow, results-based curriculum and assessment system, though recently modified, still seems to dominate rather than teachers and schools collaboratively taking responsibility for the learning of all

- The need for schools to develop and take responsibility for involving all in Inclusive Education Policies

- All staff need twin-track accredited training on inclusion in general and impairment specific accommodations for running an inclusive classroom

- Not allowing LSEs for more than a year destroys continuity; changing teachers and LSE’ each year is very disruptive

- The Education Directorate needs to have regular meetings with MFOPD to discuss issues before decisions are taken

- The need for a whole school approach to academic progress through UDL and evidence-based positive behaviour support

- There should be more push in services into mainstream schools and classes rather than pull out

- A primary focus of the inclusion process should be building relationships between non-disabled and disabled peers and more involvement of disabled individuals and their parents in decision making

That said, Malta has many examples of good inclusive practice, accessible schools and a willingness to improve, which should embarrass the former colonial power – the United Kingdom, whose Government seems determined to reverse Inclusion in England.

Richard Rieser

Richard is General Secretary of the Commonwealth Disabled People’s Forum and Director of World of Inclusion

![Allfie [logo]](https://www.allfie.org.uk/wp-content/themes/allfie-base-theme/assets/img/allfie-logo-original.svg)