Leadership, culture and resistance

Disability History Month 2019 is nearly upon us. Our theme is Disability: Leadership, Culture and Resistance. We hope more and more schools, colleges, community groups and workplaces will learn about the transformation of thinking about being disabled, which heralded fundamental positive changes in disabled people’s lives in the 80s and 90s. Unfortunately, we have gone into reverse since 2000, with marketisation and austerity.

Over the last 150 years, the radical history of disabled people, leading to improvements in the conditions of our existence, has been shaped by handfuls of individual disabled people, their thinking and movements which challenge the status quo. This status quo is shaped by the system’s requirements for employment, profitability and needs of an increasingly globalised market, mediated by humanitarian and charitable impulses and occasionally the outcomes of the self-advocacy of the disability movement.

Ben Purse was a blind piano tuner who had trained at Henshaw’s Blind Asylum, Warwick Road, Old Trafford. Purse was born in 1874 and had lost his sight completely by the age of 13. After failing to get work for two years Purse decided to form a radical organisation of only blind and partially sighted people. Purse and the newly formed National League of the Blind (1899) argued the need for an entitlement to direct state aid and the abolition of all charities. Purse was a strong advocate of self-representation and using parliamentary and direct action, arguing a trade union was required in order to represent workers who were being exploited both in private industry and in the charity sector. The NLB joined the TUC in 1902 and the Labour Party at its first Conference in 1906, which endorsed the NLB policies including adequate education and training for blind students in mainstream institutions. In 1920 the NLB organised three marches on Parliament from the South West/Wales, Newcastle and Manchester to converge on London to win a guaranteed minimum wage. They organised many strikes, one for 6 months in Bristol in 1912. Organisations such as the NLB and its influence in the TUC and Labour Party helped frame the Beveridge Report and the instigation of the Welfare State.

The introduction of the Welfare State ironically led to an increase in segregated provision for disabled people in long stay mental deficiency hospitals, asylums and care homes and a rapid growth of segregated education. The 1944 Act was based on selection by ability for Grammar, Secondary Modern and Technical schools, with increased selection for disability with 14 new categories of special schools. This was matched by the growth and increased professionalisation of special educators and rehabilitation professionals.

A very useful and readable resource is ‘No Limits’ by Judy Hunt (2019) which recounts the historical transformations for physically disabled people from institutional care to independent living. Being married to Paul Hunt, one of the pioneers of the Disabled People’s Movement, Judy can draw on Paul’s journal and papers and has interviewed the dwindling number of Paul’s contemporaries*.

In the 1950s those with significant physical impairments were placed in hospital wards for the chronically sick and elderly, as there were too many obstacles to them living their life in the community. The root cause of their problem was seen as their impairment, but Paul came to think the social and physical barriers to his integration were the key problem. These barriers were underlain by deep and age old prejudicial oppressive attitudes and thinking. Le Court was set up by Leonard Cheshire as his first alternative home for ‘the disabled’. There was an easy-going attitude with residents being fairly free to pursue their interests and relationships. There was also a democratic residents’ committee, controlling a publication ‘Cheshire Smile’ and a film-making unit. However, as local authorities were paying for places at the growing number of these residential homes, they increasingly exerted pressure to have stricter management with petty rules and to medicalise these institutions. At Le Court, Paul and the other residents resisted these pressures collectively over a long period, even being threatened with expulsion back to hospital. Out of these many local struggles Paul and others produced the important book ‘Stigma. The experience of disability’(1966), analysing their experiences and arguing for a different approach to the ‘medical model’, self-representation and control of their lives. In 1972 Paul, having married Judy and moved to his own adapted home in London was to write a letter to the Guardian which led to the formation of the Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS).

“I am proposing the formation of a consumer group to put forward nationally the views of actual and potential residents of these successors to the workhouse. We hope in particular to formulate and publicise plans for alternative kinds of care”.

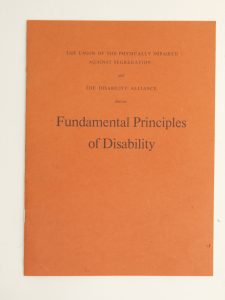

Paul and Judy met Vic Finkelstein and his wife and ideas cross fertilised. Vic had been imprisoned in South Africa for anti-apartheid activity after he was paralysed. Vic was one of the key thinkers credited with developing the idea of disability as a social oppression and positing the social model**. In an article before his death he says that this thinking took much from the struggle for race equality in South Africa. UPIAS went on to recruit disability activists from across the UK and formulated the Fundamental Principles of Disability***. This led to the setting up of the British Council of Disabled People and the formation of Disabled People International, in which Finklestein played a key part.

“In our view, it is society which disables physically impaired people. Disability is something imposed on top of our impairments, by the way we are unnecessarily isolated and excluded from full participation in society. Disabled people are therefore an oppressed group in society. It follows from this analysis that having low incomes, for example, is only one aspect of our oppression. It is a consequence of our isolation and segregation, in every area of life, such as education, work, mobility, housing, etc.”

Ken and Maggie Davis, two leading members of UPIAS, pioneered independent living, commissioning their own housing scheme in Sutton in Ashfield. After four years including buying the land, working with architects and bringing in adapted fittings from Sweden, they moved in 1976.

The Disability Liberation Network were more influenced by the Women’s Movement. Following their initial meeting at Lower Shore Farm outside Swindon in 1980, they focused more on breaking down isolation by finding ways to communicate with each other whether deaf, blind or physically impaired. Many of the ideas that were developed by Micheline Mason and others in their ‘In From the Cold’ magazine helped later form the Alliance for Inclusive Education. Work on self-representation, social model and disability as an oppression were brought together to transform education at a founding conference of the Integration Alliance in 1990****.

Some principles of the Disability Liberation Network

- To seek to abolish all forms of segregation particularly in education settings and residential institutions

- To seek allies amongst able bodied people (i.e. people who will help us fight for ourselves-not on our behalf)

- To seek complete self-determination and control over our representation in the media and to have control over information put out about us.

- To encourage people with disabilities to organise themselves into active groups which will discuss the implications of achieving their rights at international, national and local levels, and will seek to change or influence conditions around them.

- To make allies of, and be allies to, all oppressed groups.

Our movement needs more than ever to go back to these insights to find new ways of struggling for inclusive education and equality. There needs to be a recognition that on paper and in law we have made progress, but that our experience of the deeply ingrained oppression towards all disabled people requires us to be directly and collectively involved in a transformation of society and the world. We can make a start by challenging the growth of exclusions and special free schools being promoted by the government.

Richard Rieser

World of Inclusion

Resources:

References:

*** https://the-ndaca.org/resources/audio-described-gallery/fundamental-principles-of-disability/

![Allfie [logo]](https://www.allfie.org.uk/wp-content/themes/allfie-base-theme/assets/img/allfie-logo-original.svg)