Advancing School Transformation from Within

David Towell and Gordon Porter look at how good schools are transforming culture, organisation and practice to ensure all students are present, participating and achieving.

In his great book, Creative Schools, Sir Ken Robinson invites us to consider afresh the fundamental question: ‘What is education for?” His answer is that the aim of education is to enable students to understand the world around them and their talents so they can become fulfilled individuals and active, compassionate citizens. If our schools are to achieve this goal, we must promote schooling with 1) a broad and flexible curriculum, 2) creative and personalised approaches to learning, and 3) a culture which celebrates the full range of diversity among youth. Inclusion Now readers know this!

But we also know that to deliver this vision in practice is challenging and very few places across the globe have achieved what we can understand as an inclusive education system. Over thirty years, the Canadian province of New Brunswick has developed a very supportive policy context for advancing inclusion (see Inclusion Now 47). In many other places the context isn’t so supportive. But either way it is the schools themselves that have to do the serious work of transforming culture, organisation and practice to ensure all students are present, participating and achieving. To complement our previous study, we have produced a new guide to how good schools are doing this.

We invited leaders (parents and advisers as well as teachers and principals) in eight such schools that we know to tell us their story. We chose these case studies from a divergent range of political and cultural contexts: three from New Brunswick; three from countries in South America and two from London. Of course the level of resources of all kinds available in London is considerably different from those in La Paz, Bolivia. But we think there are many common features both in the values and the processes involved in transformative change.

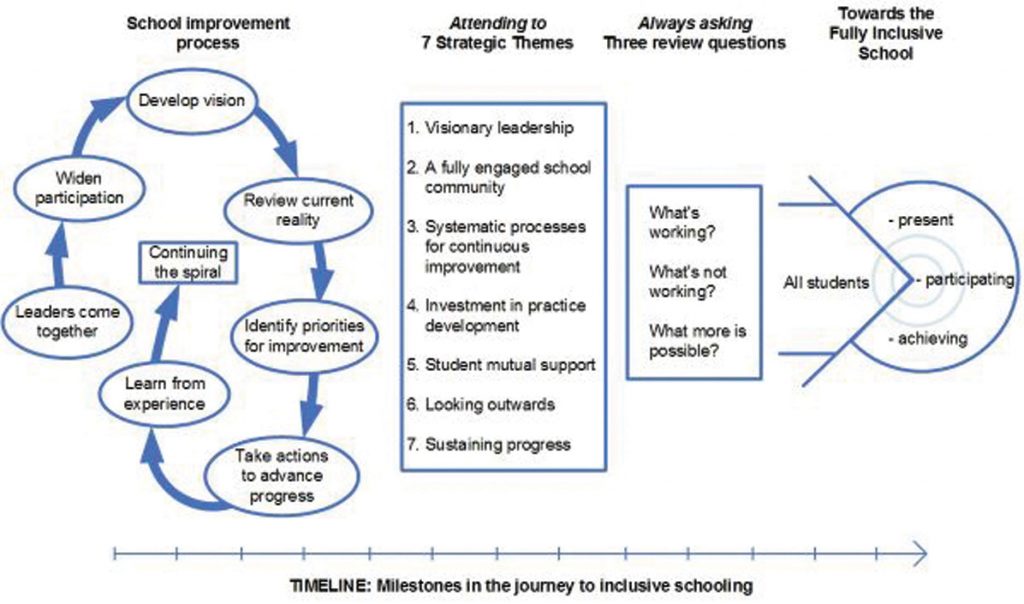

We have summarised these common features in the form of the diagram below. Our guide elaborates on all of these with examples from the case studies. Here we can highlight five key elements.

Schools are small – and sometimes not so small – communities embedded in wider networks and communities, especially the larger education systems and localities from which students, families and many staff come. School transformation requires the active engagement of the whole school community. Inclusion is everybody’s business and fellow students are the critical resource.

There are many possible drivers for change. Some initiatives start outside the school, for example in new legislation or the organised pressure of families; others start inside, for example, in new leadership articulating inclusive values or the need to respond to more diversity in student admissions. In all, transformation involves a lengthy and more-or-less systematic process of school improvement which we represent as a spiral in the model. Leaders of various kinds come together to take responsibility for shaping the future and invite wide participation in exploring opportunities for change, clarifying the school vision and taking actions, small and large, to close the gap between ideals and current experience.

To advance this spiral, the vision needs to be expressed in concrete ways like the 16 indicators of whole school and classroom performance in UNESCO’s Reaching Out To All Learners.

Many things may need to be done to improve the school’s physical accessibility, provide teaching assistance and obtain necessary aids to learning, but the critical investment is in practice development, focused on class teachers. We are talking here about flexibility in the curriculum, Universal Design and self-directed learning as much as differentiated instruction and individual adjustments. This is not so much a question of teacher training but rather of creating a continuous learning community among school participants.

David Towell & Gordon Porter

Case study: developing inclusive education in Newham

The borough of Newham in East London is the most ethnically diverse local authority in the UK and one of the poorest. Despite widespread “disadvantage” children in the borough’s schools achieve above national averages based on the government’s measures of attainment.

In 1986 the local council adopted a policy of inclusive education and over ten years closed six special schools and set up a system to support all schools to include all children and young people. The main thrust of the policy was that children would attend their local school from the early years. Most of the children transferring from the special schools moved to their local schools and in addition, “resourced schools” were established.

Resourced schools were a response to some parents’ concerns about children being separated from friends and also from teachers who knew them and their support needs well. So, gradually as the special schools closed, some resourced schools were set up. Resourced schools receive a budget allocation for a specific number of children (between 10 and 15 in a primary school and around 30 in a secondary school) with high support needs. They employ additional teachers and support staff. Today fifteen resourced schools support around 250 children and young people with complex autism and profound and multiple learning difficulties and the overwhelming majority of children and young people attend their local schools.

The policy was developed on the basis of a human rights approach to education. The council realised that it was bizarre to continue to segregate children and young people on the basis of impairment labels. By the early 1980s there was enough evidence of the negative outcomes of segregation that the council was very keen to make sure all children were included in their communities and that the whole population became aware of the benefits of learning and living together. Segregation had led to social isolation and unfulfilled lives and the local community was not benefitting from the contributions of learning disabled citizens.

Each school had to learn how to include previously segregated children and young people and they rose to the challenge brilliantly. The most common comments were that it was just about good teaching and learning and person-centred practice. It soon became clear that inclusion led to better, more humane schools which also improved when measured against government attainment targets.

Cleves primary school and Eastlea secondary school are both inclusive schools resourced to include children with “profound and multiple” learning difficulties in addition to local children with the whole range of impairments.

Eastlea was covered in Inclusion Now 45. Cleves primary school was newly built and specifically designed to be accessible for all. Children are empowered to support and care for each other and it is a real privilege to witness how very young children are naturally inclusive and giving when adult attitudes do not get in the way. The first head teacher was specifically appointed to run an inclusive school and of course then all of the staff knew that they were coming to work in a school which included children with complex additional needs. Cleves is one of the highest achieving primary schools in the country proving that an inclusive school in a “disadvantaged” area can be excellent on every measure and dispelling the myth that including disabled children has a negative impact on other children – quite the reverse.

At the time of writing inclusion is under threat as the UK government’s policies are not supportive. There is now an enormous emphasis on academic attainment and nationally it seems to have been forgotten that academic content accounts for a minority of learning in schools. Children learn a lot from the other young people they spend time with as well as from teachers. We learn the skills of friendship and social relationships and our moral values are challenged and shaped. We learn about sex and hopefully, we have fun. But we also learn about power and control and how to have a voice when things are not right. Children and young people with additional needs have the human right to be included in the rough and tumble of ordinary life. Schools don’t have to be perfect before disabled children are allowed in. They simply need to be good and to have an ethos that everybody belongs and be willing to find out what works from people who have trodden the path before.

Linda Jordan

![Allfie [logo]](https://www.allfie.org.uk/wp-content/themes/allfie-base-theme/assets/img/allfie-logo-original.svg)