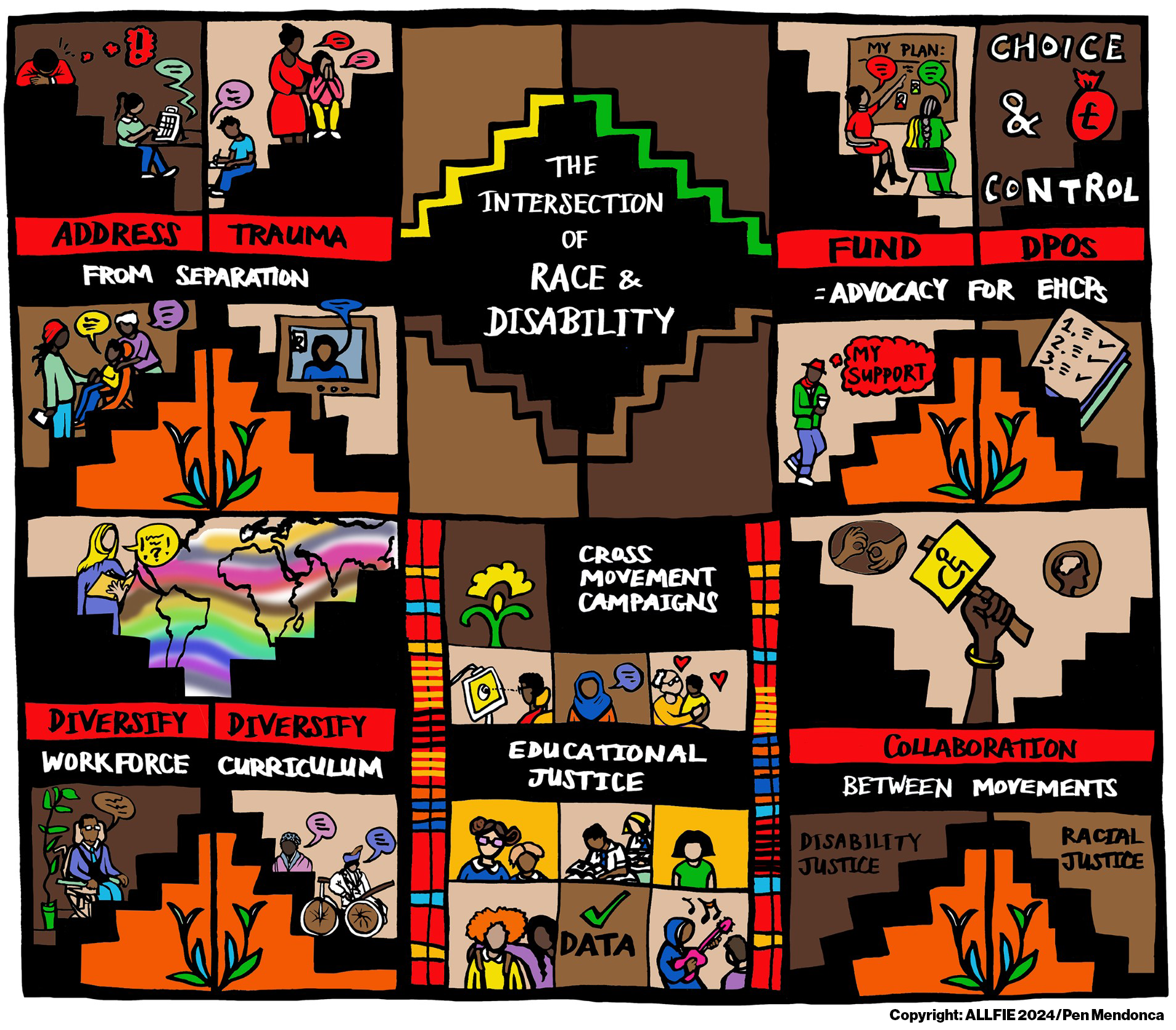

Lived Experience of Black/Global Majority Disabled Pupils and their Families in Mainstream Education

ALLFIE’s research project about the lived experiences of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils and their parents about schooling. It explores experiences of mainstream school placement, participation, support and attitudes of school staff, and makes important recommendations to address issues.

- Download full report (pdf): Lived Experiences of BGM Disabled Pupils in Mainstream Education

- Easy-read pdf: EASY-READ Lived Experience of BGM Disabled Pupils in Mainstream Education

- Summary pdf: SUMMARY Lived Experience of BGM Disabled Pupils in Mainstream Education

Table of Contents

Summary

This research is about the lived experiences of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils, aged 11-16 and their parents about schooling. It explores experiences of mainstream school placement, participation, support and attitudes of school staff.

The research found that there is inadequate support for Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils and their families in terms of advocacy, peer support to share information and provide clarity on entitlement, help to empower them and protect children’s right to mainstream education.

Children and young people told us that they would like;

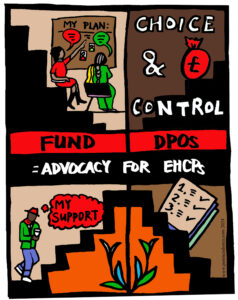

- To have better choice and control over their support, so as to be better able to join in and participate in the range of school activities and opportunities.

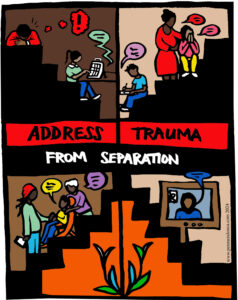

- An end to the separation of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils and recognition of their proud intersectional experiences, not ones based on deficit.

- To have a say in writing school rules and policy, to coproduce practice and build a sense of belonging.

Parents highlighted their concerns to us in terms of;

- That they feel they have little support and limited or no choice about where and how their children are educated.

- An excessive use of disciplinary procedures and practices of surveillance towards Disabled pupils and Black children that result in negative consequences or exclusion.

- Difficulties navigating an education system that is complex and often overlooks intersectional experiences of disability and race.

The current lack of support makes it hard to address any tensions around the intersections between disability and race when navigating the education system. To address these issues, we make the following six recommendations.

Recommendations

- Improve understanding and recognition of intersectional experiences.

Increase the representation of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils within the education setting and social justice work. - Tackle the trauma experienced through grouping and separation.

Encourage work in schools to address the effects and trauma caused by segregation on all pupils. - Promote independence, choice and control in EHCPs.

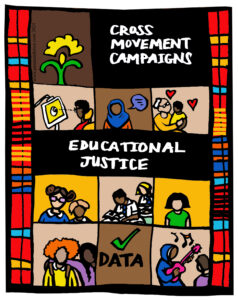

Develop advocacy support to ensure EHCPs achieve independent living and human rights of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils. - Challenge negative attitudes and promote positive representation.

Diversify the teaching workforce, profile more diverse experiences in school and promote learning about intersections of disability and racial justice. - Expose harmful disciplinary procedures and surveillance.

Build a campaign between disability and racial justice organisations to highlight and end disciplinary procedures that lead to exclusion and discrimination of young people. - Challenge segregation, promote participation.

Highlight school intake discriminatory practices affecting Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils, showcase practical and applied solutions that demonstrate how inclusive education can and does work elsewhere.

Acknowledgements

The Alliance for Inclusive Education (ALLFIE) Research Steering Group would like to thank the Runnymede Trust for commissioning a research study which explored the educational experiences of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils (aged 11-16) and their parents. Your support has been instrumental in driving this project forward, and your commitment to advancing research in this area is appreciated.

We also thank Disabled Black Lives Matter (DBLM)[1] for offering their expertise, support, time and commitment to engage in conversations about this research. They have provided direction and offered a critical voice and meaningful debate about research questions and emerging issues. We wish to extend our gratitude to note-takers and Karima Ali (a former project researcher).

We want to express our sincere gratitude to all stakeholders and research participants (Disabled pupils and their parents) within the London region. This research would not have been possible without their support, and we hope that the issues raised in this report show that their lives matter. We are sincerely grateful for their participation.

Finally, we acknowledge the context in which the issues raised in this report reflect the broader struggles for disability justice by Disabled Activists, campaigners and scholars and the continuing battle for inclusive education.

ALLFIE Research Steering Group

- Dr. Navin Kikabhai, Chairperson of ALLFIE, (University of Bristol)

- Dr. Themesa Y Neckles, DBLM member, (University of Sheffield)

- Tasnim Hassan, Trustee of ALLFIE and PhD Student/Researcher (Durham University)

- Michelle Daley, Director of ALLFIE

- Saâdia Neilson, Disability Justice Consultant and DBLM member

- Iyiola Olafimihan, Disability Justice Consultant and DBLM member

- Okha Walcott-Johnson, Disabled Children and Parent Advocate and DBLM member

[1] Disabled Black Lives Matter is a group of people that campaign to address racial and intersectional inequality of Black Disabled people. DBLM, who situated themselves alongside Black Lives Matter, aim to encourage other Disabled People’s Organisations (DPOs)/movements to aim for racial and intersectional equality.

List of Abbreviations

ALLFIE: Alliance for Inclusive Education

AP: Alternative Provision

DBLM: Disabled Black Lives Matter

DPO: Disabled People’s Organisation

EHCP: Education, Health and Care Plan

ESN: Educationally Subnormal

ITE: Initial Teacher Education

PRU: Pupil Referral Unit

SEN: Special Educational Needs

SENDCo: Special Educational Needs Disability Coordinator

SEND: Special Education Needs Disability

TA: Teaching Assistant

UNCRPD: United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

Glossary of Terms

Ableism is based on a hierarchy of ability through notions of able-bodiedness (and able-mindedness); favouring, valuing and normalising the standards of non-disabled people.

Black/Global Majority Rosemary Campbell-Stephens coined the term to promote a sense of collective belonging while addressing the inappropriateness of terms like BAME/BME. Black/Global Majority serves as a unifying term to change understanding and language regarding individuals from Black, Asian, Brown, dual-heritage, indigenous to the global south, and those racialised as ‘ethnic minorities’ (source: https://www.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/-/media/files/schools/school-of-education/final-leeds-beckett-1102-global-majority.pdf).

Disability is often understood as a problem, a tragedy, and often about something that is ‘wrong’ with a Disabled individual. It is a consequence of society’s failure to accommodate the entitlements and rights of Disabled people. The social model of disability interprets disability as discrimination, exclusion and social restriction. Disability as discrimination involves identifying barriers and oppression and recognising power relations.

Disabled people/persons/pupils is an identifying and collective term for a group of people with impairments who identify as Disabled people.

Disabled People Organisation (DPO) is an organisation which is run and controlled by and for Disabled people, and centres lived experiences, uses the social model of disability to address disablism and ableism and applies the UNCRPD.

Disablism is a consequence of disability discrimination—oppressive or abusive behaviour based on the belief that Disabled people are inferior to non-Disabled people (source: https://demos.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/files/disablism.pdf, p.9).

Education Health and Care Plan (EHCP) covers individuals from birth to age 25. This legal document outlines the educational needs and arrangements necessary for a child to enable children/young people to access education and achieve their goals.

Inclusive Education, also called ‘inclusion’, embraces the idea of education that includes everyone, promoting a learning environment where non-disabled and Disabled individuals, including those labelled with ‘Special Educational Needs,’ learn together in mainstream schools, colleges, and universities (source: https://www.allfie.org.uk/definitions/what-is-inclusive-education/).

Independent Living Disabled people are in control and can choose how they care for themselves.

Intersectionality is the idea that different social categories, such as race, class, gender, and disability, interact to produce various experiences.

Learning Support Assistants are individuals allocated to support the learning that takes place in classrooms. This support can be provided in one-to-one situations or small groups. Their role may also involve assistance with tasks such as reading, feeding at lunchtime, or attending to medical needs. These tasks vary and depend on the individual pupil’s needs.

The Medical Model of Disability typically views Disabled people as a problem and tends to label individuals by using medical and pseudo-scientific terms. Disabled people are viewed as disabled by their impairments (e.g., blindness, deafness, wheelchair-user or autism). An objective of the medical model of disability is to cure a person’s impairment, often through medical interventions. When using the medical model of disability, the question of how a Disabled person fits into society would disappear. This approach suggests that society does not need to change to accommodate Disabled people, reinforcing discriminatory attitudes and behaviours. https://www.allfie.org.uk/definitions/models-of-disability/medical-model-disability/

A Personal Assistant (PA) is a person employed by a Disabled individual to assist with tasks, including getting dressed, socialising with friends; enabling the person to achieve independent living and live in their community.

Pupil Referral Units (PRU) / Units / Alternative provisions are segregated provisions designed outside the mainstream schooling system and intended to not place pupils in mainstream schools.

Racism happens when others treat people negatively because of their skin colour, ethnicity or nationality. There are different types of racism, such as institutional, direct and indirect racism. For example, direct racism could be calling someone horrible and hurtful names based on the colour of their skin. Institutional racism creates systemic barriers that disadvantage others because of the colour of their skin, ethnicity or nationality. Indirect racism (discrimination) can occur, for example, when there are policies that apply to everyone but disadvantage a group of individuals because of their skin colour, ethnicity or nationality.

Social justice concerns systemic and structural societal inequalities, addressing equity, equality, inclusion, access, quality, rules, and values and promoting difference and well-being for all people.

Social Model of Disability, a term coined by Mike Oliver in the 1980s, provided the understanding that Disabled people are seen as disabled not by their impairments (such as blindness or autism) but by society’s failure to take their needs into account. (source https://www.allfie.org.uk/definitions/models-of-disability/social-model-disability/).

Special Educational Needs and Disability, ALLFIE defines Special Educational Needs as relating to Disabled individuals regarding the requirements and arrangements for additional educational support.

Special Educational Needs and Disability, in legislative terms, is defined as that which calls for ‘special educational provision’ and a young person is said to have ‘learning difficulties’ if they have a ‘greater difficulties than the majority of children of the same age’ or ‘has a disability which either prevents of hinders the child from making use of educational facilities of a kind provided for children of the same age’. Disability is defined as ‘physical or mental impairment which has a substantial and long-term adverse effect on a person’s ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities. For Disabled people, these definitions are inconsistent and problematic and typically place the ‘problem’ of disability within the individual. (refer to Disability above)

A Teaching Assistant (TA), sometimes referred to as a Learning Support Assistant, is a person who usually assists with all elements within the class and works more closely with the classroom teacher. Their role may also involve reading, assisting with feeding at lunchtime or attending to medical needs. These tasks vary and depend on the individual pupil’s needs.

Territorialised boundaries are associated with the theorisation of space and can be of multiple forms (for example, cultural, of the body, identities). Territorialised boundaries and spaces, related to geopolitics and globalisation, often involve disputes (sometimes violent) and arguments which reflect power struggles. It can affect the role of states and sovereign power. Segregated educational spaces are routinely territorialised, involving vested interests and issues of subordination and power.

Velcro support is a term which describes the possible adverse effect of the role of a TA or LSA who has been assigned to an individual. In this situation, an adult TA or LSA often becomes a barrier, preventing the young person from making friendships with their peers or engaging in everyday interactions by being ‘stuck together’ and not giving space. Velcro support often prohibits more natural peer–support relationships occurring in and outside of schools amongst their peers.

Introduction

This small-scale qualitative research aimed to critically examine the lived experiences of Black/ Global Majority Disabled pupils in the mainstream education system. ALLFIE, a DPO, conducted this research, and its members formed a research steering group of Black/Global Majority Disabled people with lived experience. We intended to understand the disproportionate impact of a failing education system on the often-ignored lives of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils through their intersectional experiences. Our positionality centred on ALLFIE’s social justice approaches to the social model of disability, disability, lived experience, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disability (UNCRPD) (on Inclusive Education, Article 24) and intersectionality.

The report encompassed focus group interviews with parents and Black/Global Majority Disabled school-aged children. Through participants’ lived experiences of attending a mainstream school setting, this report acknowledges how their lives are directly affected by systems of disablism and racism. It adds to the current inclusive education debates, challenges existing inequalities within the education system and seeks to improve outcomes for Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils.

Given the issues raised in this report, it is essential to acknowledge how disability is framed. For example, in the field of inclusive education, there is an overarching focus on how the ‘requirements’ and ‘needs’ of Disabled pupils are met to enable them to achieve their potential. According to Runswick-Cole (2008) and Beckett (2009), these discussions are framed within an ongoing discourse between a medical model (which focuses on the individual’s impairment and is deficit-driven) and a social model (which prioritises the removal of barriers). This report adopts the position that ‘disability’ is ideologically constructed (Kikabhai, 2022) and that it is the organisation of society that disables people. As Oliver (2009) articulated, over two decades ago:

… the barriers disabled people encounter include inaccessible education systems, working environments, inadequate disability benefits, discriminatory health and social support services, inaccessible transport, houses and public buildings and amenities and the devaluation of disabled people through negative images in the media – films, television and newspapers (Oliver, 2009, p.47).

This report recognises that currently, how various stakeholders seek to improve school life, educational environments and the way multi-agencies work together (e.g., parents, local authorities, health and social care services, Integrated Care Boards [ICBs]) to accommodate various ‘differences’ (Naraian and Schlessinger, 2017) is contested. Indeed, as the literature review highlights, there is increasing segregation under the guise of so-called ‘Alternative’ provision (HMSO, 2023).

Alongside critically examining the lived experiences of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils’ schooling, the research investigates the intersection of disability and race within this context. This report aims to understand how Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils and relevant stakeholders navigate their educational experiences by identifying connections and themes to enhance the inclusive education movement.

The remaining section of this report focuses on a review of related literature; the methodological approach adopted, key findings and a discussion of the data and recommendations.

Literature Review

This literature review explores the importance of school placement, Education, Health and Care plans and raises critical questions about the continued and persistent inequalities in the education system. In this sense, the Special Educational Needs Disabilities (SEND) system has become even more adversarial and bureaucratic. The review also explores the issue of teachers’ attitudes towards racial equality and draws attention to the problem of representation, or lack thereof, within the teaching profession. The review explores disciplinary procedures and surveillance of behavioural policies and their connection to Disabled people’s experiences of restraints. Finally, this literature review refers to social participation and its relationship to how Disabled people are perceived.

School Placement and Intake

Since the start of modern mass state schooling, school placement for Disabled People and those currently described as having Special Educational Needs has a long history of segregation (Humphries and Gordon, 1992), often in the guise of treatment (Kikabhai, 2014), which later shifted to a discourse of needs (Borsay, 2005; Haines and Ruebain, 2011). Research related to school placement tends to focus on parental choice (parental preference in legal terms) between special educational provision and mainstream settings (Satherley and Norwich, 2021; Bagley et al., 2001; Bajwa-Patel and Devecchi. 2012). There are several vital factors framing this dualistic debate. These include a school’s willingness to accommodate a child’s educational needs, the availability of resources, the special educational teaching (pedagogy), class size, quality of parents-school communication, parents’ and teachers’ attitudes, the proximity of the school to home, and the well-being of the child (Rix and Sheehy, 2014; Mawene and Bal, 2018).

Being a signatory (and ratifier) to the UNCRPD (United Nations, 2006), the United Kingdom has placed a Reservation on Article 24, which primarily means that ‘special’ education is part of its offer. Of course, this contradicts the United Nations’ requirement for Member States to demonstrate the progressive realisation of inclusive education. The UNCRPD (United Nations, 2006) states that Disabled students participate in mainstream settings and have equal access to private and public educational institutions.

Nevertheless, persistent educational barriers exist, including unfair assessments of children’s abilities, exclusion, and inadequate resource allocation, impeding children’s access to mainstream education (Runswick-Cole, 2008; Soorenian, 2019). Moreover, as stressed by Kikabhai (2022), a recent United Nations observation drew concerns about the continued dual education system that segregates Disabled pupils based on parental choice. Compounding the issue of resource allocation, funding for mainstream schools has also been heavily influenced by performance-based criteria and meritocracy.

Research by Leckie and Goldstein (2018, p.22) highlighted that ‘the higher the proportion of disadvantaged pupils in a school, the more [the school] will effectively be punished for the national underperformance of pupil groups.’

Alongside the concern about the UK’s Reservation on Article 24, the number of Disabled pupils in so-called ‘special’, ‘alternative’ and ‘free’ schools has increased as thousands of new special school places were confirmed (Dept for Education and Coutinho, 2023). For example, the UK Government’s (UK GOV, 2023) latest figures for 2022/23 indicate that in England there has been an increase of 87,000 pupils said to have SEN, the percentage of pupils with an EHC plan increased to 4.3% from 4.0%, the percentage of pupils with SEN but no EHC plan has increased to 13% from 2.6%.

Arguably, the increasing number of segregated provisions deprives Disabled pupils of their right to a fully resourced inclusive education system. There is a disproportionate number of Disabled and Black pupils enrolled in segregated school environments. The early work of Coard (1971) identified this trend, using the notion of ‘educationally subnormality’ and how Black Caribbean children were disproportionately placed in ESN settings during the 1960s-70s.

This trend continues in a modified form known as SEND (Skiba et al., 2008; Wallace and Joseph-Salisbury, 2022). In addition, the recent SEND and Alternative Provision Improvement Plan (HMSO, 2023, p.9) introduces National Standards as an approach to delivering funding bands and tariffs.

These standards suggest that Disabled pupils labelled with complex needs are more likely to be placed in a segregated ‘special’ school as a result of these new funding bands and tariffs. A pressing concern arises around how this approach to schooling inadvertently perpetuates racism and ableism. This is because the evaluation of children for admission to special schools is linked to schools’ subjective assessment of pupil’s behaviour, emotions, and communication levels.

Experiences of Education, Health, and Care (EHC) Plan

An Education, Health, and Care (EHC) Plan is “a legal document which describes a child or young person aged up to 25 special educational needs, the support they need, and the outcomes they would like to achieve” (Council for Disabled Children, 2023, p.1). Cochrane and Soni (2020) examine the experiences of implementing and using the Education, Health, and Care (EHC) Plan, emphasising the growth of multi-agency working, which remains complicated and disjointed. This captures many positive experiences and challenges, including parental involvement. Whether the processes genuinely centre children and young people, evaluate the role and knowledge of school staff, and recognise disparities in experiences based on age and different educational stages is still debatable.

Despite aspirations to adopt a holistic approach with the EHC plan, it has been criticised for its reductionist and deficit-oriented characteristics, with a notable omission of the environmental aspect (Hunter et al., 2019). The implementation of the EHC plan faces challenges. For example, families’ access to a Personal Budget from Local Authorities to meet their child’s needs lacks transparency, and schools are expected to grapple with this process unsupported (Adams et al., 2017; Blatchford and Webster, 2018; Cochrane and Soni, 2020).

Given the significance of the Government’s SEND and Alternative Provisions Improvement plan, it is disappointing that the report failed to take an intersectional approach. However, it is noted that the report did ‘highlight some disparities concerning certain characteristics such as place, gender and race’ (HMSO, 2023, p.43). The report notes their absence in these areas. It fails to point out the consequences of homogenising Disabled people and their families to a singular characteristic and social background, as well as the way this report is implemented.

The report has committed to using the Regional Expert Partnerships to engage ‘… the voices of all children and young people with SEND or in alternative provision and their families are effectively heard, and no group is disadvantaged …’ (HMSO, 2003, p.43). This is particularly disconcerting, especially given that as of June 2023, ‘Travellers of Irish heritage’ and ‘Black Caribbean’ students had the highest prevalence of individuals with EHCPs.

There has also been a constant increase in appeals challenging EHCP-related decisions. A consistent trend emerges when examining the outcomes of SEN/D tribunal appeals, as 96% of the outcomes in the 2021/22 period were in favour of the appellant (same as the previous year). Notably, this does not make any reference to race or ethnicity.

Teachers’ attitudes, competence, and workforce

Research indicates that teachers in mainstream educational settings generally have a positive, inclusive attitude. However, its implementation needs to be revised. For instance, Center and Ward (2006) highlight that there is a lack of confidence in being able to provide support, and Avramidis and Norwich (2002, p.129) emphasise that there is ‘no evidence of acceptance of a total inclusion or ‘zero reject’ approach’, finding that this is selective. About diversifying the curriculum and supporting diverse needs, there has been a notable surge in the desire to promote racial equality (Klein, 1993; Hall, 2021; Batty et al., 2021). However, despite this increased interest, it has become increasingly evident that educators lack the confidence and training to implement more diverse content effectively (Petitions Committee, 2021; Joseph-Salisbury, 2020). Perhaps even more ignored, references to disability remain relatively minor and not given appropriate consideration, as pointed out by Beckett (2009).

Further, Kikabhai (2022) suggests that within diversity work, not only is disability intentionally ignored, but it is also silenced and erased. It has been felt that staff have had limited training to support inclusion – particularly in universal learning design (Dolmage, 2017). This highlights teachers’ considerable challenges, including time and training limitations and insufficient guidance in addressing ‘challenging’ or ‘sensitive’ subjects. In light of this, the University of Manchester and Runneymede Trust’s Making History Teachers briefing (Lidher et al., 2023) highlights the urgent requirement for the Department of Education to establish structures enabling extensive professional development for all educators.

Enhancing teacher training is crucial to prepare and support teachers adequately. For example, Lidher et al. (2023) underscore the necessity to update both the Teachers’ Standards and Initial Teaching Education (ITE) with a more substantial commitment to addressing anti-racism, inclusion, and diversity issues. It is known that there are significant tensions with ITE when it comes to Disabled people and so-called ‘Fitness to Teach’ standards that often act as a barrier rather than an enabler to the teaching profession, particularly for individuals who identify as having mental health difficulties (differences), experience distress, identify as neurodivergent individuals, and/or are survivors/users of mental health/psychiatric services (Pattinson and Kikabhai, forthcoming).

There exists poor representation within the teaching workforce, which is linked to lowered expectations for Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils. For example, there is a ratio of one white teacher for every 13 white pupils. In contrast, a stark imbalance exists of one Black teacher to every 42 Black students, exacerbated in other domains and senior roles (Hillman, 2021; Wallace and Joseph-Salisbury, 2022). It is necessary to question that both of these datasets lack intersectional overlap and knowledge regarding whether teachers are Black/Global Majority Disabled people. There is also an omission of disability data obtained for teachers (Office for Statistics Regulation, 2023). Hence, it can be strongly inferred that there is a significant lack of educators with diverse and intersecting experience.

Disciplinary procedures and surveillance

There are other inequalities in behavioural policy. There are three specific groups of children and young people who are disproportionately affected by behavioural policies in schools, namely, those identified as having SEND, individuals from racially diverse communities (including Black students and those from Gypsy, Roma, and Traveller backgrounds) and students from under-resourced backgrounds (Gillborn et al., 2013). Between 2018 and 2022, in England and Wales, data from the Children’s Commissioner revealed at least 2,847 documented strip-searches of children conducted in schools and outside schools before arrest under stop and search powers, with the report highlighting a significant six-fold over-representation as 38% of the strip-searched children were Black, a group constituting 5.9% of the population (Dodd, 2023). This is compounded by the Child Q scandal and the perpetuation of negative stereotypes through Prevent Duty (Home Office, 2023; Runnymede, 2023; Zempi and Tripli, 2022). Additionally, law enforcement has been assigned to areas ‘with higher numbers of pupils eligible for free school meals, which correlates with higher numbers of Black and ethnic minority students’ (Runnymede, 2023, p.2).

Disabled students have a higher probability of being subjected to restraint or seclusion in school, as indicated by recent reports indicating that 88% of reported incidents involved children or young people, including students identified as having SEN/D (The Challenging Behaviour Foundation, 2019; Hodgkiss and Harding, 2023). Regarding monitoring the use of restraints in schools, the Equality and Human Rights Commission inquiry (Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2021) highlighted confusion and inconsistency in school restraint policies; schools varied in how they record restraint incidents, especially in distinguishing between types.

Many are uncertain about specific forms of restraint, and some do not promote categorising incidents by protected characteristics. Additionally, as Worth (2013) highlighted, Disabled students can be heavily monitored by supporting [sic] staff in controlled environments. Interestingly, Ktenidis (2023, p.1) contends that some problems associated with TA support relate to structural inequalities that recreate exclusion. Further still, Ktenidis (2023), drawing upon the experiences of Disabled students in secondary school, makes the point that TAs carry out their duties ‘under the guise of support’ and often aim for normalisation. It has been known that there are disadvantages to using TA support. For example, Gerschel (2005, p.71) referred to the ‘velcro’ model in terms of recognising the possibility of students becoming emotionally dependent on the TA.

Social Participation

A crucial aspect of school life involves social inclusion, as frequently depicted in literature through attitudes, approval, a sense of belonging, and the formation of friendships (Carter and Hughes, 2005; Petry, 2018). Attitudes towards disability significantly shape whether Disabled students receive more positive or negative experiences (Freer, 2023). Research tends to be more skewed in highlighting persistent barriers, irrespective of the type of education setting, such as challenges developing meaningful friendships, experiencing bullying and exclusion due to being perceived as different, non-disabled peers reluctant to befriend Disabled people and those labelled as having SEN, feelings of isolation, and a lack of opportunity (Shah, 2007; Edwards et al., 2019; Woodgate et al., 2020; Helman, 2009; Batorowicz et al., 2014).

Despite this dominant narrative, researchers such as Avrandis (2012) and Shah (2007) evidence some positive experiences. A recurring message emphasises the significant role that inclusivity-focused environmental elements, such as school staff and resources, can play in mitigating marginalisation (Baker and Donnelly, 2010; Anaby et al., 2012; Avranidis, 2012).

In summary, while it is evident that additional efforts are needed to address the educational barriers experienced by Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils, young people and their parents, this review aimed to highlight emerging issues that could provide insights into their experiences.

Multiple layers contribute to shaping the experiences and narratives relevant to this group. Institutionally, neoliberal, pursuing profits, and systemic deficit-driven inclinations affect the availability of support and the procedures for obtaining it and, consequently, shape student placements and intake and entitlements under the EHC plan.

This influence extends to the teaching workforce and various agencies, characterised by punitive and controlling practices aimed at achieving ‘normalcy,’ a lack of confidence, and enforceable legislation in supporting diverse student requirements and limited literacy regarding issues of race and disability. These factors collectively contribute to a societal narrative that detrimentally affects Disabled students’ overall sense of belonging within mainstream educational settings.

Methodology

This section explains the methodological approach that was adopted during the research. It presents its conceptual frame, which primarily describes how knowledge is gained. It also discusses online focus group interviews, the analytical approach, and research ethics issues. We were interested in critically examining the lived experiences of schooling for a small group of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils in the mainstream education system.

Conceptual Framework

The research adopted an interpretivist perspective within a philosophical and conceptual framework of social constructionism (Burr, 1995), using focus group interviews as the sole method of data collection. We were particularly interested in gathering qualitative data to understand the lived experiences of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils and their parents about mainstream schooling.

We were interested in challenging taken-for-granted ideas about schooling, seeking to understand the daily interactions of pupils and parents with schooling staff, recognising that these are socially, culturally, and historically situated. In Berger and Luckaman’s (1991) terms, we are interested in the social construction of everyday life, and in this context, with an analysis of schooling, particularly about how the lives of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils and their parents are constructed.

Focus Group Interviews

Fitting within adopting social constructionism, focus group interviews allow participants to ‘… articulate those normally unarticulated normative assumptions’ (Bloor et al., 2001, p.5). As such, we were keen to understand the barriers, challenges, strategies and participation experiences of the individual participants and their collective experience.

The two online focus group interviews were arranged with four (4) Black Disabled young people/children aged 11-16 years of age and three (3) parents of Black Disabled pupils/young people. Initially, potential participants were recruited through social media and parent networks. Greenbaum (1998) said these focus group interviews would be more accurately termed mini groups. Uniquely, each of the online focus group interviews, mini groups, were facilitated by four members of the research team; this included an interviewer (moderator), a safeguarding lead who was available if any of the participants felt they wanted time-out and somebody to talk to, a timekeeper, a coordinator who provided technical support and a notetaker.

All participants were sent a focus group interview schedule (Appendix D). Both online focus group interviews lasted approximately 60 minutes and were digitally recorded and transcribed. The digital recordings were sent to a professional transcription service for verbatim transcripts. All focus group participant names were anonymised, we recognised the cultural sensitivity around using appropriate pseudonyms rather than engaging in acts of cultural and identity (agency) erasure.

Analysis

Once verbatim transcripts were available, key themes were identified across and within each of the transcripts. The research adopted critical discourse analysis to focus the group on topics, ‘… tapping into group life …’ (Bloor et al., 2001, p.50), searching for similarities, noting differences, and particularly interested in analysing social and political inequalities.

Ethical Considerations

Participants were provided with an Information Sheet (Appendix B) which described the purpose of the research, what the participation would mean, how participant data would be protected and stored, reassurance about the confidentiality and anonymity of the data, and participants’ right to withdraw without having to provide a reason.

All focus group participants were sent a consent form (Appendix C) before participating in the research. Online focus group interviews were recorded via Zoom and stored in password-protected folders on ALLFIE’s server. Issues of confidentiality were particularly stressed during online focus group interviews.

During focus group introductions, the interviewer stressed this particular point; the specific focus Group interview extract is:

Extract: FG160623

11 … In terms of confidentiality, I’m sure you

12 would appreciate that, given that we’re going to be talking as a group,

13 we may not know each other. And so, therefore, after the focus group,

14 we would ask you to refrain from talking about the contents of this

15 particular interviews with other people. And I’m sure you’ll be close to

16 other people and it’ll probably be very tempting to talk to somebody

17 and if you needed to talk to somebody, please reach out to us again

18 if you just needed to debrief or anything like that. …

Another ethical consideration was the late arrival of one of the pupils and their parents, who had connected via their mobile phone network during their focus group interview.

This caused some intermittent network failure and delays in re-connectivity. Fortunately, technical support was available to assist and facilitate reconnection.

Findings, Analysis and Discussion

The main priority of the findings, analysis, and discussion is to develop knowledge about the experiences of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils and their parents in mainstream education to inform campaigns and advocacy that take a social justice approach. This section focuses on five issues drawn from the findings and offers a discussion and analysis in conjunction with the previous literature. The five issues relate to school placement, experiences of EHCP, teacher attitudes, disciplinary procedures and surveillance, and social participation.

School placement and setting

Pupils provided insightful reflections on what it is like to study alongside non-disabled peers within a mainstream setting. Noeline made a notable observation that highlighted the importance of how she conveyed her findings about the separation of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils and their exclusion from the larger school community.

To illustrate this point, Noeline raised the following:

… there’s a person in year seven uses a wheelchair, but I don’t see them around that much.

(Noeline, Focus Group Interview, 2023)

Noeline continued to elaborate on the extent of separation between the pupils, with some of the Disabled pupils being placed in different parts of the school building, with required authorisation, explaining that:

[There’s] a place where wheelchair and Disabled pupils go there, and nobody’s allowed there, it’s locked… Like only there’s, there’s not a buzzer. The teacher has to get the card.

(Noeline, Focus Group interview, 2023)

This is worrying, as Kikabhai (2023) noted. These territorialised boundaries, part of the landscape of social power, maintain social order and control. It seems that the effect of this practice creates internalised oppression that reinforces the marginalisation of racialised and non-racialised Disabled people.

Our discussions with parents largely revolved around the parents’ decision-making process and their experiences throughout the school journey. Parents’ experiences primarily presented the main barrier to admission to mainstream school was compounded with them having to position a more impairment-specific priority, disregarding the intersections of disability, race, gender and other experiences of their Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils.

This is highlighted in parents’ decisions in determining an appropriate school for their children based on the school’s SEND services and support (Rix and Sheehy, 2014; Mawene and Bal, 2018).

This point was notably clear from Omnira’s experience:

I went through a process of choosing the school, so I contacted the schools I thought would be good for them, and what I looked for was their SEND and Provision Department. So, what does their special needs department look like? What do they do? How educated are they in terms of SEND? So, I contacted the schools on my list, and I did like a process of elimination. I chose what I feel is the best of the worst. I don’t feel any school really encompasses what it is to be a disabled child because I don’t think that it’s personalised and it’s just based on their systems. (Omnira, Focus Group interview, 2023)

It is also noted that parents’ attempt was not to negate considerations pertaining to their child’s race, gender and social class background in their search for a school. Omnira explained it this way:

… I didn’t look at their experience in terms of ‘race’. I looked at it in terms of practice in the school practice because I couldn’t look at it as ‘race’ because there’s no commonality between us, there’s no education between us, so I couldn’t, and I didn’t know any other disabled children that were Black that was in that school. (Omnira, Focus Group interview, 2023)

This indicates that these parents’ experience navigating the SEND system defaulted to suit White Disabled pupils.

This was also compounded by a lack of peer support for Black parents of Disabled pupils, as highlighted by Njoki:

I think at the time, what I didn’t have was a good network in terms of other parents who had additional needs, and for me, I think that was probably the biggest thing because, actually, that is a really good indicator when you talk to people about the actual experiences.

(Njoki, Focus Group interview, 2023)

Zina’s strategy involved searching online and tapping into social networks, and what is particularly significant is hearing from shared experiences of the support received that ultimately helped inform their decision:

Once I’d had my eyes set on that started looking at their SEND programme and what their SEND legislations they had at that school. I also have a friend who’s a Social Worker, and she recommended the same school to me. She said, ‘ One thing I can say about that school is their SEND team is amazing’. And then, when I went and spoke to them as well, I experienced the same. I felt like, based on what they were telling me, based on what they said, that they had and what they could offer, it was a great school, and this was all before my son even had his diagnosis, but I was like pretty sure he was [going to] get it. (Zina, Focus Group interview, 2023)

It was also important for some parents that their children enrolled in a school that was also attended by other family members, which plays a vital part in reinforcing a social sense of belonging and relationships, as mentioned by Zina:

I saw one of my cousin’s sons … he had just started Year 7 when my son was in Year 6, and he was going to a school that he really, really liked and he and my son are quite similar, even though he’s not autistic, they have similar interests and quirks, so to speak.

(Zina, Focus Group interview, 2023)

None of the parents in the focus group had considered the idea of placing their children in special schools: their first choice gravitated towards choosing mainstream education, as demonstrated by multiple parents:

I’ve never considered anything outside of a mainstream school. (Zina, Focus Group interview, 2023)

… my son’s never been to anything other than a mainstream school. (Njoki, Focus Group interview, 2023)

I wanted them [twins] to be in mainstream school because I didn’t believe that being in a special school was going to be adequate for them based on how their needs were present. (Omnira, Focus Group interview, 2023)

In conclusion, the findings reveal distinct perspectives on the issue at hand. From the pupils’ point of view, a noticeable sense of separation and differential treatment emerged as significant themes. When considering the parents’ experiences, it became evident that their primary criterion for choosing a school for their Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils was the school’s SEND services, often overlooking the complex intersections of disability, race, gender, and other experiences.

It was also noteworthy that the experiences of Black/Global Majority parents of Disabled pupils were faced with limited choices available to parents, whether this was from lack of information or peer support networks. From this, the evidence demonstrates that schools often dictate the selection of the child, rather than parents having a say in choosing the school, a point articulated almost two decades ago (Tomlinson, 2004).

Experiences of EHCP and receiving support

Out of the four pupils, it was noted that 3 of them had EHCPs with access to a Teaching Assistant (TA) and other support services. Notably, all three pupils raised concerns about the implementation of their EHCPs. One of the concerns echoed the principles of the Independent Living Movement, which emphasises the ability to choose and control your support. It also became evident through the focus group interview with pupils that their support staff needed to share their experiences, particularly regarding shared backgrounds and interests. For example, Iskander spoke about the issues that led to the breakdown in the relationship between them and their TA. For Iskander, it appeared that the breakdown of the TA support extended to supporting a different football team; he said:

Basically, I would just like [choose Teaching Assistant]. I would. … like him to be that I would like him to support Liverpool. (Iskander, Focus Group Interview, 2023)

There were also concerns that the TA did not fully understand the support needs of pupils. For Iskander, it was particularly annoying when they did not get their entitlement to the support they needed; he specifically said:

Yeah, [I was] really annoyed … he would help me with my work. Like what I found with recent TAs is that they don’t like every time I want, like, every time I ask them for a walk, they always… And I and I don’t really like that. That’s one of the main reasons why I didn’t get along, obviously.

(Iskander, Focus Group Interview, 2023)

Iskander’s experiences with his TA aligns with the point raised by Whitburn (cited by Ktendis, 2023, p.4) that TAs ‘perpetuate the special education traditions in inclusive education’, highlighting limited agency and lack of centring the student’s voices in their support.

Interestingly, Whitburn (2013, p.158), from an Australian context, found that one of the significant shortfalls of TA support (paraprofessionals) is that school cultures tend to adopt discourses of deficit and that ‘educators’ tend to rely on TAs because their own ‘shortcomings in non-inclusive pedagogical practices’.

Additional concerns were the frustration of getting a teaching assistant and sharing this provision with other pupils, which impacted their support.

Iskander articulates the issues this way:

So basically, yeah, they [the TA] wouldn’t give you space. They would always like. They would always be on to you, and they would never like… if you ask for help, they’ll cut you off. And then and then they’ll go. And then they’ll go to another student. (Iskander, Focus Group Interview 2023)

Eta, who did not have an EHCP, shared her experiences of the barriers and challenges that they were experiencing at school. When asked about the ideal person to support them in school, Eta said that they would like:

Someone who listens and understands what you say and tries to explain things in different ways is kind and funny and doesn’t keep us behind [during the] break [period]. (Eta, Focus Group Interview, 2023)

Regarding parents’ involvement and experience with the EHCP planning, experiences were varied. For example, not all of the parents’ children had an EHCP; some were currently going through the process, and another parent was assessing the situation to help decide the appropriate action to take. Zina shared that:

… We’ve recently had a… handover meeting with the person that assessed my son and his school SEND team and his Head of Year. And we had a meeting about what he needs and what I’m asking for, etcetera, and they were very helpful. They seem very open, and they already suggested things there, and then they’ve really put certain things in place. He doesn’t have a plan. I do think we will go for that eventually, but he’s doing okay. He’s doing okay. (Zina, Focus Group Interview, 2023)

Njoki, another parent, recounted their journey of implementing their child’s EHCP and conveyed, “My son has an EHCP, and that has been helpful, and it was perfect for him.”.

Njoki elaborated on their experiences, highlighting the complexities involved in this process. She particularly emphasised the challenges encountered during the transition from primary to secondary school, which introduced distinct structures, mechanisms, and considerations related to the EHCP implementation.

Njoki disclosed that:

So, because he was at [primary] school, that was already well built and suited to his needs, if that makes sense. So yeah, they had a really good, you know, ethos across the school, in terms of, you know, supporting children of additional needs. … It’s a very nurturing environment. His teacher is, I think she’s trained as a SENCO … So, for example … [it] wasn’t articulated in the EHCP that he needed one-to-one … I realised when he transitioned…he needed one-to-one … but then when we moved to school, certain issues would start to arise. Even though we’d had a transition meeting with this one, had articulated that these are the provisions that were in place, then the school actually hearing that and doing that because of course, we know that, you know, so the section I say we not everyone does. But what I’ve learned is that section F is really crucial to pinning down some of those things that, you know, your child may need, and I think in terms of that transition process when you’re moving to a school, that. The reality is you don’t know how your child is going to respond… You can do as much research as you can on all of those things, but actually, when they move into that setting, you know they’re then faced with changing lessons every 50 minutes. You know, and all of these different factors. It’s a completely different setting, and so, therefore, what you’ve got in the EHCP is really important… And anyway, that was my experience. (Njoki, Focus Group Interview, 2023)

In summary, the preceding sections have delved into the experiences of both pupils and parents as they navigate the educational system, particularly concerning the practical aspects of EHCPs. In the context of pupils’ experiences, the significance of having a choice and control over their support staff has been highlighted. However, it is noteworthy that the actual implementation of TAs tends to be more aligned with special educational practices.

Turning to the parents’ perspective in this section, many nuances have been observed in their decision-making processes, particularly during the transitions from primary to secondary school. It also highlighted instances of intersectional erasure, such as race, disability and other background characteristics within the education system. This showed up in the way parents considered the type of support they anticipated that their child would be receiving while at school. This differentiation manifests in numerous ways; it would require consideration of factors such as class sizes, subject-specific variations, alterations in the learning environment, adjustments to timetables, and more – all of which collectively influence a student’s daily schooling experience.

Teachers’ attitudes, competence, and workforce

Pupils extensively discussed their perceptions of teachers’ attitudes and the curriculum and consistently believed their voices went unheard. When asked about what kind of teacher would be preferred, Nyima expressed that:

And maybe a teacher that would actually listen to students and, erm, give in to students’ needs. Someone that listens and actually cares about their work and my education. (Nyima: Focus Group Interview, 2023)

Iskander reiterated the feeling and expressed the desire to have teachers listen to him and be more relatable:

Like someone who listens, like someone who can actually understand what you mean and… relate to your feelings, and someone who actually like gives you time to talk because a lot of teachers cut you off. Yeah. (Iskander, Focus Group Interview, 2023)

Hillman (2021) and Wallace and Joseph-Salisbury (2022) highlighted the issue of underrepresentation within the teaching workforce. Eta expressed a sense of detachment and lack of enthusiasm in their interactions with teachers, characterising their experiences with educators as ‘boring’.

Pupils had diverse experiences regarding the curriculum’s presentation, especially when learning about different cultures, history, and related topics. To illustrate, Eta shared her perspective on a lesson that was part of Mental Health Awareness and how she felt about the school’s delivery of the topic; she expressed that “it was very helpful” (Eta, Focus Group Interview, 2023) to understand people’s different and various experiences. During this conversation, it became evident that this lesson for Eta helped facilitate a discussion with some of her friends. Asking Eta about these discussions with her friends, she replied by noting that there was nothing ‘weird’ about discussing differences or feelings with her friends, when it came to mental health needs/support. Specifically, Eta replied:

A little bit [a conversations with friends], but not in a weird way. (Eta, Focus Group Interview, 2023)

When asked about whether and how difference was taught in school, Nyima was not able to account for this being done well, she replied:

No, not really, but like the history about women, I think I learned that in citizenship [lesson] sometimes (Nyima: Focus Group Interview, 2023)

It was apparent that none of the pupils were able to share school experiences when they received a lesson that had examples of Black/Global Majority Disabled people.

As pointed out by Lidher et al. (2023) it has been demonstrated that when pupils encounter depictions of individuals like themselves (whether through the teaching workforce or curriculum), it significantly influences their perception of their role in the world. Although pupils mentioned a few instances of diversity, these seemed extremely rare, raising concerns about representing intersecting experience.

Regarding parents’ perspectives, their responses varied when discussing diversity, support, and the representation of teachers and the workforce. For Zina, diversity within the school was significant in that:

When he [was] diagnosed… I said I specifically want[ed] a male Black mentor, and they [were] able to do that at the drop of the hat. They had a male Black, they had a few, you know, Black mentors in the school that do like physical education with them, etcetera, etcetera, they have. (Zina, Focus Group Interview, 2023)

When questioned about the presence of Disabled teachers, Zina could not identify any, emphasising the one-dimensional nature of representation and diversity in this context. Njoki also reflected on the role of representation in that:

… I think it’s really important and I know I haven’t really spoke about it that much, … around representation and how actually, particularly for Black children and Black boys. You know, just really how important it is to have that because that has been a challenge that wasn’t a part of the challenge when telling him about his diagnosis, how he was able to process them. (Zina, Focus Group Interview, 2023)

These discussions revealed that disability was not given priority when considering diversity. Indeed, according to Kikabhai (2018), discussions of diversity cut across educational sectors.

Interestingly, parents placed a greater emphasis on meeting specific needs when selecting schools, but when it came to the workforce and the teaching and learning environment, the focus leaned more toward racial considerations, often without considering both aspects with an intersectional approach.

Disciplinary procedures and surveillance

The matter of disciplinary procedures and surveillance was linked to pupils’ perceptions of what makes a teacher ‘bad’, with much of it stemming from a sense of rigid rules and approaches that lead to a lack of fair and respectful treatment and a feeling of not being understood. Eta described a poor teacher as:

Someone who keeps us behind at the break, someone who doesn’t listen or like, pay attention, or like help out – I guess. But, like, they don’t really teach; they say off the board. (Eta, Focus Group Interview, 2023)

Iskander reflected on ow the TA treated him, how the TA would ‘touch’, ‘push’ and ‘poke’ him, and interestingly connected this to wanting to be believed by referring to his peers, a friend and his classmates, who were witnesses to the TA’s questionable behaviour. Iskander also made a further plea to ‘check the CCTV’, he explained it this way:

My teaching assistant, I told him never to touch me again from start touching a lot like it’s like, like, just like pushing me out of the way and then he started poking me on my shoulders, and it really hurt. And then, even my friend [friends name], my best friend, [they] said that [they] saw as well and all of my other classmates and we saw as well, and then when they check the CCTV. (Iskander, Focus Group Interview, 2023)

It was clear from Iskander’s comment how the TA’s behaviour significantly undermined any sense of respect, and how this took away his agency. What Iskander highlighted was the TA’s approach, which involved exerting substantial control and misusing their authority while claiming to offer support: This situation becomes noteworthy because it emphasises Iskander’s need to support this encounter by having evidence. Continuing this, Noeline talked about her experience with teachers who labelled her fidgeting as a distraction and how teachers assumed she was not paying attention.

There is a frustration that teachers do not believe her and do not take her word seriously:

… like, sometimes, like most of the teachers do this well, I’m like playing something in my hand something or like a pen, and they’re like, “Oh, you’re not listening”. But I am listening, right, I’m actually listening. So I’m too confused cause I’m saying I’m listening to them, but they don’t even listen to me. (Noeline, Focus Group Interview, 2023)

It becomes evident that the nuances of pupils’ impairments, such as differences in communication styles or movement habits, were overlooked. Consequently, these nuances, dynamics of power, often get misinterpreted as misbehaviour, leading to a significant sense of misunderstanding and frustration. This, in turn, frequently prompts the disciplinary measures taken against pupils and increased surveillance.

The persisting issues of racial and disability injustice within school disciplinary procedures and surveillance are a concern to the parents. Their concerns are supported by the constant reporting of school exclusion, which is disproportionately high for Disabled pupils and Black boys (Gillborn et al., 2013; Runnymede, 2023; Ktendis, 2023; DfE, 2019). There was also a sense of over-controlling in some schools used to manage children’s behaviour to fit into a particular socially constructed idea. When asked about the feeling of a controlling element within school regulation, Njoki shared that:

… a lot of the time, these secondary schools tend to be when they’re faced with particular behaviours that they either don’t understand, don’t want to understand, or don’t want to have to deal with. It can be very sanction-heavy. (Njoki, Focus Group Interview, 2023)

Njoki went on to provide more insight, emphasising the concerns her son had regarding his behavioural issues at school:

… some of the behaviours that he has, he was anxious and distressed or whatever the case is, would be difficult to manage and then they’re responded to by staff in ways that are not always ideal. You know the number of times he comes home and things that have been said, and I’ve had to raise him at the school. And all sorts of different things about how, you know, he’s responded to. (Njoki, Focus Group Interview, 2023)

The transition between primary to secondary school settings and their accompanying rules can present a challenge for some Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils. This aspect of adapting to new rules and environments has often been overlooked, especially in the context of disciplinary procedures and surveillance.

Njoki highlighted:

… I think especially when the secondary, there’s this expectation that children move from primary where it was a much more nurturing environment, you know. Things are much more sort of friendly, and then they’re immediately immersed into a system that is, but that can sometimes be very rigid in expectation … It becomes evident you engage with it. (Njoki, Focus Group Interview, 2023)

What is evident from the experiences of both pupils and parents regarding disciplinary and surveillance methods is the use of a standardised approach to disciplinary procedures and regulations, which neglects the nuances of impairments. The treatment pupils receive also results in substantial distress, ultimately undermining the school’s role as a safe, respectful, and genuinely understanding environment.

Social participation

Regarding social participation in school, pupils discussed their experiences from interactions with other pupils, a sense of well-being and peer acceptance. Friendship responses varied, with one student highlighting a positive relationship and shared interests with their TA. They found the new TA to be more compatible, leading to improved working:

OK, so how [does] my teaching assistant work? It’s basically I do all my (inaudible) things, but he’s with me in the class. Basically, I meet him at first period, and then I do my phone and everything, but on Monday mornings, I have this thing called Enrichment. And I played football … with all my friends, like basically, so I played football. A team, so I got chosen (inaudible). Like, he likes everything that I like, he likes football. Fine. And then all my friends get along with them [teaching assistant] as well, so it’s fun to have them [teaching assistant] around. And he’s one as well. Like he’s like, he’s funny as well. (Iskander, Focus Group Interview, 2023)

Pupils also recognised the reciprocal nature of meaningful relationships rather than the often-perceived notion that they are the sole recipients of care/support. It was equally important to be able to give and receive support. When asked how they support another student, Noeline responded, “… with their work” (Noeline, Focus Group Interview, 2023).

None of the pupils referred to having role models or were aware of any Black/Global Majority Disabled individuals they could recognise as sources of positive support for their values and identity, both within and outside school. This observation aligns with the earlier discussions on the importance of representation and perception.

Parents had varied responses when it came to their children’s social participation. They particularly emphasised friendship, using it as a gauge to assess their child’s sense of belonging and acceptance among their peers. Some parents shared their children’s friendship experiences, drawing from conversations or information their children provided. These reflections shed light on how the parents interpreted their child’s relationships:

His issue is … making friends and sustaining friendships. (Zina, Focus Group Interview, 2023)

So, he has a wide network of people he socialises with at school. Everyone is his friend. What that looks like in practice is a slightly, you know, might be quite up for questioning. But, he generally gets on quite well with lots of different children. (Njoki, Focus Group Interview, 2023)

I didn’t realise that until we were invited to a party in year five. Normally, their party is like everyone else’s, mainly maybe two or three friends; the rest are cousins, cousins, cousins, and friends. So, I never really got to see interactions outside of that until we went to a party, and I felt so bad for her. I just assumed that you know, interact with everyone else kind of how she does when she’s with the family, and she didn’t. She really, really didn’t. Her sister was more, children more go to her sister and adults go to her. (Omnira, Focus Group Interview, 2023)

Once again, drawing a connection to the curriculum and the diversity of content also contributes to establishing friendships and developing more meaningful social participation. It becomes crucial for parents when their child can identify with individuals who have a shared experiences, as mentioned by Omnira:

… there was nobody at school that she could identify with… And so I would search for books and programmes but again, there are not many programmes that are targeted to Black children with these conditions …. (Omnira, Focus Group Interview, 2023).

Pupils and parents provided valuable insights into friendships, belonging, and acceptance dynamics. Pupils conveyed the diverse nature of their experiences, with some highlighting positive and compatible relationships with individuals. Acknowledging reciprocity in meaningful relationships emphasised the importance of giving and receiving support. Notably, the absence of recognised role models from Black/Global Majority Disabled communities was a notable observation. Parents, in turn, emphasised the significance of friendships as a measure of their children’s sense of belonging and acceptance. Furthermore, the vital role of curriculum diversity in fostering friendships and meaningful social participation became evident.

In summary, this section has highlighted the perspective of pupils and parents on the intersections of race and disability within the school life and education system. It dealt with five key areas directly related to how well schools accommodate differences, driving practices responding to racial and disability injustices, which are part of legal obligation and align to principles of inclusive education.

Conclusion

This small-scale research project focused on the lived experiences of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils and their parents about schooling. The research objective, through the use of focus group interviews, was to gain an insight into the perspective and challenges of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils and their parents about their experiences of mainstream school placement, levels of participation, support received (or lack thereof), attitudes of the school staff.

The report found that five critical areas emerged from this group of individuals related to barriers, challenges, structural inequalities, and participation in terms of teachers and support staff. There is inadequate support for Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils and their families in terms of advocacy, forums, and peer support to share information and provide clarity on entitlement, help to empower them and protect children’s right to mainstream education.

There are also very few social justice organisations interested in these areas of activism or who have created intersectional practice. The absence of advocacy support makes it hard for Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils and their families to obtain knowledge, make informed decisions, and address any tensions around the intersections of ‘race’ and disability, which often gets overlooked in the experiences of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils and their families when navigating the education system.

In summary, the findings showed that the priority for children and young people was to have choice and control over their support; this was important to them, particularly in terms of their social participation. They want an end to the separation of Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils because this reinforces stereotypes, stigma and discriminatory behaviour towards Disabled pupils. To be afforded recognition of their intersectional experiences, to have a say in writing school rules and policy, and to feel a sense of belonging.

From the perspectives of the parents, they revealed a disproportionate use of disciplinary procedures and practices of surveillance towards Disabled pupils and Black children, resulting in negative consequences, school exclusion or removal to alternative settings. For these parents, it is essential to note that none chose to place their children in a Special school. However, there was an active process of searching and navigating through the education system, which often resulted in explicit intersectional erasure of either race or disability.

The research has shown that inequalities in the educational system are not silo; it intersects with other social justice issues and international treaties of which the UK government is a signature. The obligation of the UNCRPD places a duty on our government to make progressive realisation for inclusive education (Article 24) as a right for all Disabled people. Also, with the Children and Families Act (2014), there is a presumption to mainstream education. However, the government is actively constructing a divided society, a system that is perpetuating segregation, within which specific impairment groups are being placed in alternative and segregated settings. This is far from eradicating educational systemic and structural oppression, which perpetuates ableism, racism and other forms of discrimination. Inclusive education is a human rights issue; it requires the removal of barriers and the recognition of intersectionality and cross-movement working. We have found systemic and structural barriers and injustice in the educational system.

It is the lived experiences of the Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils and their parents that this report set out to gain insights. From the identification of the emerging five areas, several recommendations are suggested, calling for a cross-movement approach for further research, capacity building on campaigns to support the shift towards inclusive education within which all children, irrespective of their intersecting identities, socioeconomic status, are not stigmatised or face discrimination.

Full Recommendations

1. Recognition of intersectional experiences

The primary concern for Black/Global Majority Disabled Children and their families is often reduced to disability only. The systemic and structural systems of discrimination (actively) ignore their racial and disability identities and neglect their other characteristics. It was evident that Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils and their families are not provided with disability justice or culturally sensitive support. The education system has poor practice on centring an intersectional approach to the curriculum and workforce, leaving many Black/Global Majority Disabled pupils without recognition and positive representation, which could help improve confidence and overall well-being.

The report recommends changes by the social justice movement, advocacy services, policy and decision-makers. These changes must ensure our campaigns embrace the global Disabled People’s Movement mantra of “Nothing About Us Without Us”.

2. Grouping and separation

Trauma experienced through grouping and separation based on race and impairment often goes unaddressed. While some mainstream school settings have adopted this practice as acceptable, and there is an expansion across the London boroughs, there is an urgent need to address its effect on student emotions and well-being. This practice is reinforcing further social stigma towards Disabled people and internalised oppression.

Trauma experienced through grouping and separation based on race and impairment often goes unaddressed. While some mainstream school settings have adopted this practice as acceptable, and there is an expansion across the London boroughs, there is an urgent need to address its effect on student emotions and well-being. This practice is reinforcing further social stigma towards Disabled people and internalised oppression.

Response: Advocacy groups working in schools and on education issues should be encouraged to address the effects and trauma caused by segregation on all pupils.

3. Choice and Control

Too many Disabled pupils are denied choice and control over their support. Disabled pupils in school should have a right to have a say over who supports them and when. There are further concerns around pooling support with other pupils, directly impacting the Disabled pupil. It was evident that this creates barriers to getting the proper support. There is a lack of advocacy support for children and families, with very few services offered by DPOs. It is worth noting that Kingston Centre for Independent Living is one of the very few London DPOs that offer an advocacy service on EHCP.

Too many Disabled pupils are denied choice and control over their support. Disabled pupils in school should have a right to have a say over who supports them and when. There are further concerns around pooling support with other pupils, directly impacting the Disabled pupil. It was evident that this creates barriers to getting the proper support. There is a lack of advocacy support for children and families, with very few services offered by DPOs. It is worth noting that Kingston Centre for Independent Living is one of the very few London DPOs that offer an advocacy service on EHCP.

Response: Local DPOs must be funded to provide advocacy support for children and families with EHCPs and their implementations to ensure it centres principles of Independent Living. This also involves developing frameworks for intersectional advocacy that stop creating hierarchies of identity to get support. This could also include working more closely with children and young people’s services.

4. Attitude and representation

The lack of representation in the workforce and the school curriculum perpetuates negative attitudes and ignorance.

The lack of representation in the workforce and the school curriculum perpetuates negative attitudes and ignorance.

Response: There is a long overdue need to diversify the teaching workforce to broaden and enrich the school curriculum. There must be a commitment to recognition for the diversification of the school curriculum that embraces both Black and Disability history. Schools should be incentivised to enable their pupils to learn about intersections of racial and disability justice. This should involve actively working with DPOs and racial justice movements. Pupils from diverse backgrounds and identities must be seen and heard in their lessons and curricula.

5. Disciplinary procedures and surveillance

The widespread use of disciplinary procedures and surveillance, which Disabled pupils and Black pupils disproportionately experience, has led to the use of restraints, being placed in seclusion, being subjected to school exclusion, being placed in alternative provision, special schools or Pupil Referral Units. There are significant numbers of Disabled pupils out of school, not accessing learning and being denied their human right to education.

The widespread use of disciplinary procedures and surveillance, which Disabled pupils and Black pupils disproportionately experience, has led to the use of restraints, being placed in seclusion, being subjected to school exclusion, being placed in alternative provision, special schools or Pupil Referral Units. There are significant numbers of Disabled pupils out of school, not accessing learning and being denied their human right to education.

Response: There is a need for collaborative working between DPOs and racial justice movements to strengthen campaigns to end disciplinary procedures and acts of surveillance that lead to exclusion and discrimination. Often, such discriminatory systemic procedures have been passed off as behavioural management strategies to control young people.

6. Social Participation