Eugenics in education and its effects on society

The legacy of eugenics in education. By Michelle Daley, ALLFIE Director, and Yewande Akintelu-Omoniyi, Our Voice Project Youth Officer

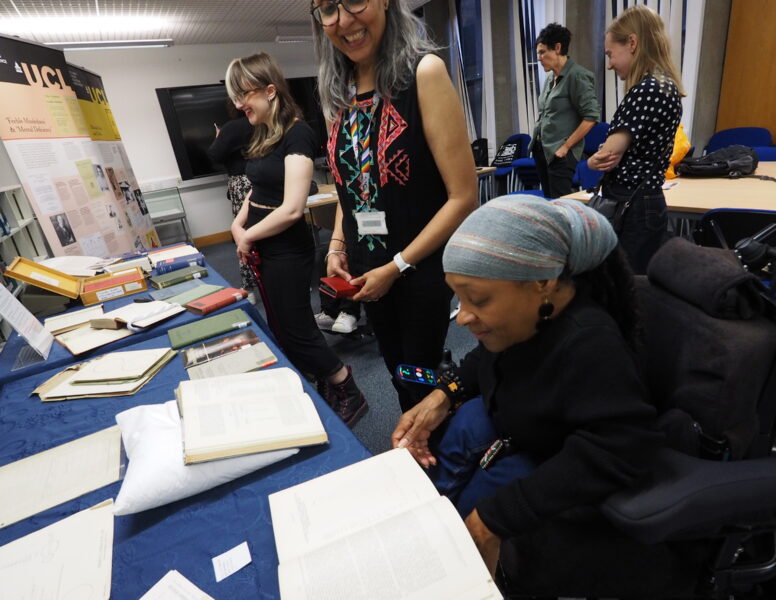

On 20th September 2023, a group of ALLFIE staff and ‘Our Voice’ youth project members attended an exhibition at University College London (UCL) on Education, Disability and Eugenics, led by a Disabled consultant, Jessica Starns. The workshop is part of a wider project called Prejudice in Power: Contesting the pseudoscience of superiority, “a programme of cultural activism for change against structural discrimination. It explores how eugenics has marginalised voices and shaped society” and how “eugenic thinking is present in the racism, ableism, homophobia and reproductive controls we see today.”

The workshop consisted of a lecture and an exhibition on the legacy of eugenics in education, and its relation to people perceived as ‘deviant’ and ‘feeble-minded’ in society. ALLFIE’s Michelle Daley and Yewande Akintelu-Omoniyi report back on what we learned.

Engineering human thinking

The work of Disabled People’s Organisations (DPO) remains significant in our campaigns on the legacy of eugenics in education and other areas impacting on Disabled people’s lives, including independent living to end segregation in all its forms. A collective of over 200 representatives from DPOs came together in a hybrid conference on 21st September 2023 at Manchester’s People’s History Museum. The conference called to increase the funding, resourcing and sustainability of DPOs, as well as cross-movement working on capacity building campaigns to dismantle deep rooted systemic injustices and inequalities. It focused on challenges in four strategic areas of The Disabled People’s Organisation Manifesto:

- Representation and Voice

- Rights

- Independence

- Inclusion

The outcome of the conference saw the adoption of the Disabled People’s Organisation Manifesto (DPO Forum, 2023) which included different asks such as “all resources going to segregated settings and programmes diverted to inclusive programmes and support”. It made clear the need to bring “a right for every Disabled learner to get appropriate support in a mainstream education setting”.

The 1900’s eugenics movement engineered a set of beliefs and practices, providing rationales to shape global thinking about the quality of the human population. Eugenicists in education were fundamental in encouraging disconnection and segregation between groups and communities. Historian, Nazlin Bhimani, from the University College London, said that eugenicist’s work was engineered in a “scientific way”, which gave acclaim to their thinking as extraordinary and had significant influence in policy and the treatment of Disabled children, and other communities considered ‘deviant’ or ‘misfits of society’. The eugenics’ movement introduced categorisation, and streaming of individuals based on ability and age to determine a child’s future potential. Eugenicists created reasonings that would result in the design of separate nurseries, schools, colleges, and university buildings to cater for children and young people, categorised by their impairments. Such reasoning led to the segregation of other groups based on characteristics such as race and socioeconomic background.

Law, policy and practice

In less than 100 years, there is enough evidence to track the tools of the Eugenics Movement in educational law, policy and practice. For example:

- 1944 Education Act introduced labelling and categorising Disabled children by their impairments. The act also placed a duty on Local Education Authorities to create separate educational places based on impairments’ groups.

- 1978 Warnock Report carried out an inquiry into the education of Disabled children. While it resulted in the ending of the 1944 educational categories of impairments and introduced the term SEN, the recommendations retained the notion of who is deserving and undeserving of mainstream education.

- 1981 Education Act and further amendments retain Local Authority power to remove Disabled children from mainstream educational settings.

- In 1992, Ofsted introduced a grading scale to inspect nurseries, schools and colleges to determine their performance and other information used from the Ofsted reporting. A setting is judged based on their grade.

- In 2009, the UK government signed and ratified the international treaty UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN CRPD) and adopted Article 24 (on Inclusive Education) as a human right. However, the government placed two reservations: on parental choice and to retain special educational settings, showing the legacy of eugenics in education.

- 2014 Children and Families Act introduced a presumption to mainstream education, and extended EHC plans between the ages of 16 and 25. The government has failed to effectively resolve these provisions of the Act.

- 2020 and 2021 Safety Valve and Delivery Better Value programmes introduced to reduce Local Authorities spending in SEND services and on EHCP’s.

- 2023 SEND and AP Improvement Plan published recommendations, which included an investment of “£2.6 billion between 2022 and 2025 to fund new places and improve existing provision for children and young people with SEND or who require alternative provision.” (DfE, 2023).

Other examples can be found in the number of Disabled children labelled with ‘complex needs’ placed in segregated residential settings that operate as both care homes and schools. There is a current campaign led by a collective of Disabled People’s Organisations, including ALLFIE, against the Hesley Group which was found to be inflicting torture and violence on Disabled children and Young people.

Influences of superiority

The above examples show how the legacy of eugenics inform current laws, policy and practice within the education system that reinforce societal divides and inequalities. The eugenics movement ideology in education continues in practices of measuring and grouping children and young people based on characteristics and socioeconomic backgrounds, by placing them into categories that influence superiority over the types of education students receive. A lot of these practices are based on assumptions about communities and groups of people in society that continues to render human difference and uniqueness as awful. The harm retained by this legacy is evident in the Timpson Review of School Exclusion but also shines a spotlight on the structural and systemic oppression in education. This particularly impacts communities and individuals who are pushed to the margins of society because of a person’s characteristics and socioeconomic background. An exploratory research conducted by Dr Ashlee Cristoffersen (2021) titled “Intersectionality in practice: Research Findings for Practitioners and Policymakers” found that “…intersectionality is widely thought to be a challenging theory to apply, and it represents a puzzle to policy makers and practitioners who work in both issue area and ‘equality strand’ silos (of e.g. race, gender, and disability)” (p.6).

It is necessary to recognise the intersectional barriers and injustices that impacts different communities and groups of people living at the margins of society. There is no doubt that the following factors are consistent with eugenicist’s ideology:

- Retaining of elite grammar schools

- Continued measuring and testing of primary school children which consists of Standard Assessment Tasks (SATs)

- Ofsted ratings on nurseries, school and college performances

- Assumptions made based on student’s personal characteristics and socioeconomic background

All are consistent with the legacies of the eugenicist’s works that we looked at during the workshop. This includes:

- Cyril Burt: An influential British psychologist who developed factor analysis in psychological testing. He believed that intelligence was hereditary, but he also believed that the environment and social background played a role in intelligence. He developed a “Backward Map of London Boroughs”, which showed the difference in intelligence across London. He was the first educational psychologist to be appointed by government, and he had a radio show on the BBC which had a lot of influence on the general population. He was also a professor of psychology at UCL from 1931- 1950. His book “Factors of the Mind” was published in 1940. After his death it emerged that his research and data had been falsified and fabricated.

- Alfred Binet: A French psychologist who introduced the first practical IQ test. The IQ test included processes such as reasoning, with techniques using, pencil, paper and different objects. He opened a laboratory in Paris for child study and experimental teaching.

- Henry H Goddard: An American eugenicist, segregationist and psychologist. His research was on intelligence and mental deficiency at the “Vineland School for Feeble Minded” in New Jersey. He brought Alfred Binet’s intelligence tests to the US. He advocated for sterilisation of people with Learning Difficulties. He manipulated the photographs of the Disabled people he photographed.

- Karl Pearson: An English mathematician and biostatistician. He was the first chair of eugenics at UCL. He promoted the idea of an “immigration IQ”. He thought that immigrants had a low IQ and he held racist views against Jewish and Black people.

- George Shuttleworth: A British psychiatrist and asylum superintendent at the Royal Albert Asylum. He introduced vocabulary and words for mental health conditions that are now part of our everyday vocabulary. Words include: ‘idiot’, ‘imbecile’, and ‘lunacy’.

- Mary Dendy: Promoted segregated education for individuals labelled as ‘mentally handicapped’ people. She established a colony for people deemed ‘feeble minded’. The aim of this colony was to keep Disabled people separated from the rest of society.

- Former Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, also believed in eugenics and judged inferior and promoted superior of human population as a way to retain a divided society. He was vice president of the first eugenics conference in 1912, which took place in London.

Arguments made by historian Nazlin Bhimani in a website article for the Wellcome Collection (2022) titled “Intelligence testing, race and eugenics” shine a light on how the history of eugenics informs contemporary society. Attention was drawn to her reference:

“The legacies of eugenics in education are most obvious in the way we continually assess our children. These methods are often based on standardised measures that result in the labelling, ranking and grouping of children”.

Nazlin Bhimani’s argument is necessary in providing an understanding of how reasons and tools were used for identifying ‘superior’ and ‘inferior’ students, which would determine the child’s educational destiny and future opportunities. Across the UK today the legacy of eugenics in education remains, with nurseries, schools, colleges, and universities competing against each other, affecting the distribution of resources and opportunities for students. As already mentioned, Timpson Review of School Exclusion (2019) highlighted the educational inequalities and intersectional injustices. Also, a recent Guardian (2023) article titled “School suspensions rise sharply among disadvantaged children in England” reported that Disabled children “were four times more likely to lose learning through being suspended”. Other literature such as 2023 SEND and AP Improvement Plan and ALLFIE’s research on School Accessibility Plans reveals the nuances of the legacy of eugenics and demonstrates its use in practice predominantly used to shut Disabled children labelled with ‘complex needs’ out of mainstream educational settings.

Inclusive education without discrimination

There are real issues with the legacy of eugenics in education and school segregation. The Council for Europe states that:

“School segregation is one of the worst forms of discrimination and a serious violation of the rights of the children concerned, as their learning opportunities are seriously harmed by isolation and lack of inclusion in mainstream schools” (2017, p.5).

Despite the UK Government being a signatory to the UNCRPD, Article 24 on Inclusive Education (House of Commons) as a human right for all Disabled people without discrimination. Yet, the education system remains committed to school segregation, further fuelled by investment to build 141 of new special schools over the next 3 years (DfE, 2023). What we are experiencing is the education system not making the efforts to ensure inclusive education for all Disabled people in nurseries, schools, colleges, and universities. The legacy of eugenics in education remains; it influences policy, parents, students, and teachers to buy into thinking that fuels marginalisation and injustices in society.

![Allfie [logo]](https://www.allfie.org.uk/wp-content/themes/allfie-base-theme/assets/img/allfie-logo-original.svg)